Interesting Science Videos

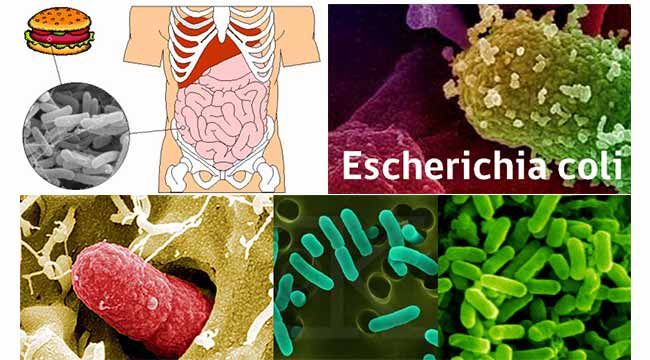

Habitat of E. coli

- E. coli was discovered by Theodor Escherich in 1885 after isolating it from the feces of newborns.

- E. coli is the normal flora of the human body.

- The niche of E. coli depends upon the availability of the nutrients within the intestine of host organisms.

- The primary habitat of E. coli is in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of humans and many other warm-blooded animals.

- It is found in the mucus or the epithelium on the wall of the intestine.

- Most commonly found in the colon of the large intestine.

- Most of them are harmless and opportunistic.

- E. coli form a mutual relationship with its host.

- E. coli helps with the absorption of vitamin K and other vitamins in the colon.

- It is the largest group of bacteria living in the intestine.

- E. coli constitute about 0.1% to 1% of GI tract bacteria.

- It is a facultative anaerobe.

- E. coli is also found in human feces.

- When E. coli is excreted from the intestinal tract, the bacteria are able to survive only for a few hours.

- E. coli is found outside the body in faecally contaminated environments such as water or mud or sediments.

- If E. coli comes in contact with raw vegetables, it has the potential to attach itself to the leaves of the vegetable.

- E. coli can also be found in environments at a higher temperature, such as on the edge of hot springs.

- E. coli is also found on ground meats due to slaughterhouse processing.

- Humans are most likely to be infected with E. coli O157: H7 found in cattle.

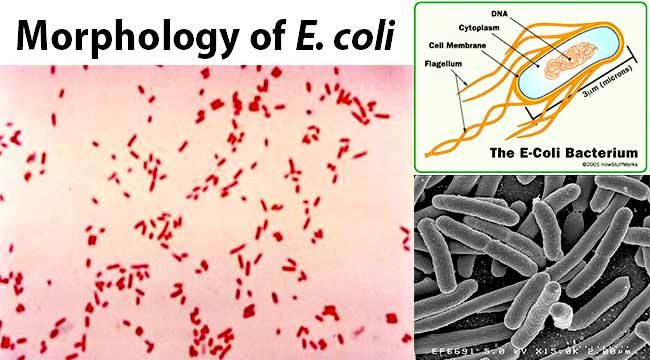

Morphology of E. coli

- E. coli is gram-negative (-ve) rod-shaped bacteria.

- It is 1-3 x 0.4-0.7 µm in size and 0.6 to 0.7 µm in volume.

- It is arranged singly or in pairs.

- It is motile due to peritrichous flagella.

- Some strains are non-motile.

- Some strains may be fimbriated. The fimbriae are of type 1 (hemagglutinating & mannose-sensitive) and are present in both motile and non-motile strains.

- Some strains of E. coli isolated from extra-intestinal infections have a polysaccharide capsule.

- They are non-sporing.

- They have a thin cell wall with only 1 or 2 layers of peptidoglycan.

- They are facultative anaerobes.

- Growth occurs over a wide range of temperatures from 15-45°C.

Antigenic Structure

- Heat Stable Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is the major cell wall antigen of E. coli.

- E. coli possesses 4 antigens; H, O, K and F.

H or Flagellar Antigen

- Heat and alcohol labile protein

- Present on the flagella

- Genus specific

- Present as monophasic

- 75 ‘H’ antigens have been recognized

O or Somatic Antigen

- Heat stable, resistant to boiling up to 2 hrs. 30 minutes

- Occur on the surface of the outer membrane

- An integral part of the cell wall

- 173 ‘O’ antigens have been recognized

K or Capsular Antigen

- Heat labile

- Acidic polysaccharide antigen present in the envelope

- Boiling removes the K antigen

- Inhibit phagocytosis

- 103 ‘K’ antigens have been recognized

F or Fimbrial Antigen

- Heat labile proteins

- Present in the fimbriae

- K88, K99 antigens

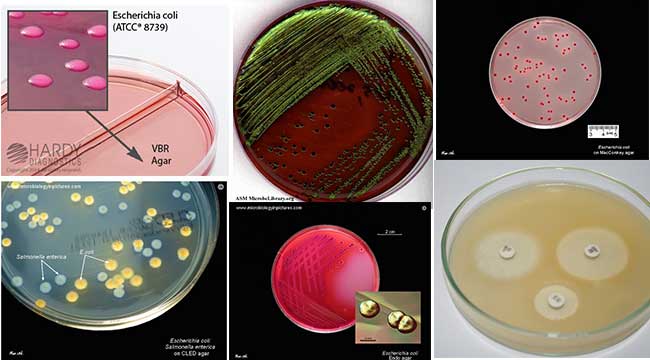

Cultural Characteristics of E. coli

1. E. coli is a facultative anaerobe.

2. Its optimum growth temperature is 37°C and ranges from 10°C to 40°C.

E. coli on Nutrient Agar (NA)

1. They appear large, circular, low convex, grayish, white, moist, smooth, and opaque.

2. They are of 2 forms: Smooth (S) form and Rough (R) form.

3. Smooth forms are emulsifiable in saline.

4. Due to repeated subculture, there is smooth to rough variation (S-R variation).

E. coli on Blood Agar (BA)

1. Colonies are big, circular, gray, and moist.

2. Non-hemolytic colonies (gamma-hemolysis) (Above Figure) OR Beta (β) hemolytic (Below Figure) colonies are formed.

E. coli on MacConkey Agar (MAC)

Image Source: Dr. Gary E. Kaiser, Community College of Baltimore County

1. Colonies are circular, moist, smooth, and of entire margin.

2. Colonies appear flat and pink.

3. They are lactose fermenting colonies.

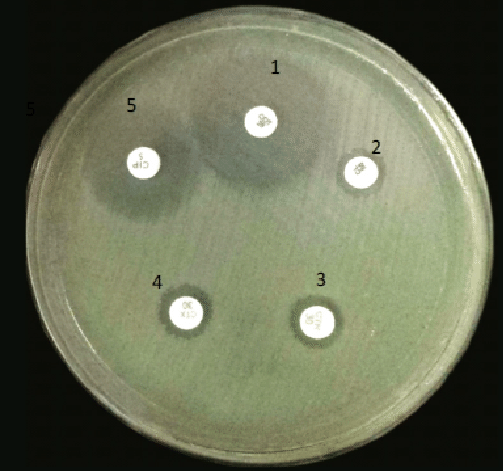

E. coli on Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA)

Image Source: Anjan Paudel, DOI: 10.4172/2327-5073.1000278

1. Colonies are pale straw-colored.

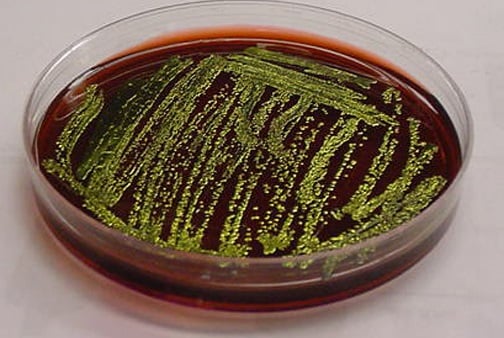

E. coli on Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB) Agar

1. Green Metallic sheen colonies are formed.

E. coli on m-ENDO Agar

Image Source: Wikipedia

1. Colonies are green metallic sheen.

2. Metabolise lactose with the production of aldehyde and acid.

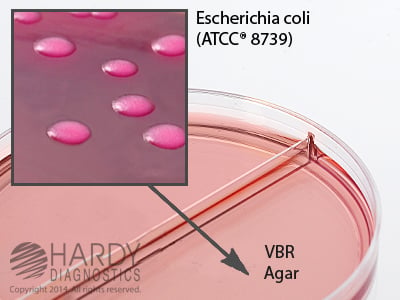

E. coli on Violet Red Bile Agar (VRBA)

Image Source: Hardy Diagnostics

1. Red colonies (pink to red) are formed.

2. Bluish fluorescence around are seen around colonies under UV.

E. coli on Cystine Lactose Electrolyte-Deficient (CLED) Agar

Image Source: Microbiology In Picture

1. They give lactose-positive yellow colonies.

E. coli on Liquid Media

1. They show homogenous turbid growth within 12-18 hours.

2. R form agglutinate spontaneously, forming sediment on the bottom of the test tubes.

3. After prolonged incubation (>72 hrs), pellicles are formed on the surface of liquid media.

4. Heavy deposits are formed which disperses on shaking.

Biochemical Characteristics of Escherichia coli (E. coli)

Pathogenicity of E. coli

- E. coli is the most common and important member of the genus Escherichia.

- It is a Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms).

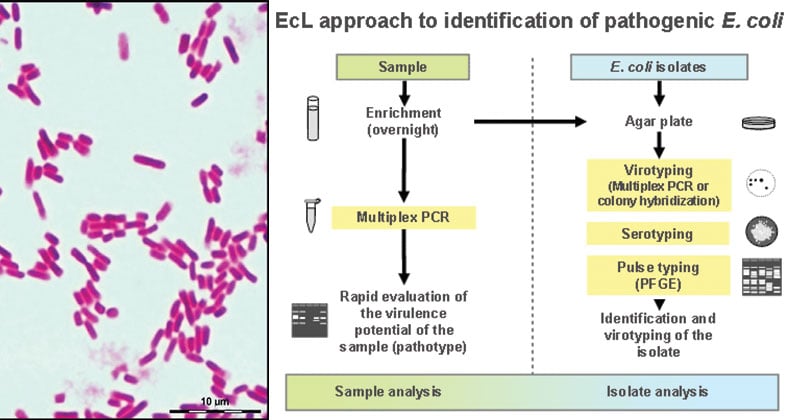

- Human Escherichia coli strains are classified as commensal microbiota E. coli, enterovirulent E. coli, and extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli on the basis of their genetic features and clinical outcomes.

- Most infections (with the exception of neonatal meningitis and gastroenteritis) are endogenous; that is, the E. coli that are part of the patient’s normal microbial flora are able to establish infection when the patient’s defenses are compromised (e.g., through trauma or immune suppression).

- This organism is associated with a variety of diseases, including gastroenteritis and extra-intestinal infections such as UTIs, meningitis, and sepsis.

- A multitude of strains are capable of causing disease, with some serotypes associated with greater virulence.

Image Source: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro818 and https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006238

Virulence Factors of E. coli

- E. coli possesses a broad range of virulence factors.

- In addition to the general factors possessed by all members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, Escherichia strains possess specialized virulence factors that can be placed into two general categories: adhesins and exotoxins.

ETEC (Enterotoxigenic E. coli)

- Colonization factor antigens (CFA/I, CFA/II, CFA/III)

- Heat-labile toxin (LT-1); heat-stable toxin (STa)

EPEC (Enteropathogenic E. coli)

- Bundle Forming Pili (BFP); intimin

EAEC (Enteroaggregative E. coli)

- Aggregative adherence fimbriae (AAF/I, AAF/II, AAF/III)

- Enteroaggregative heat-stable toxin; plasmid-encoded toxin

STEC (Shiga toxin-producing E. coli)

- BFP; intimin

- Shiga toxins (Stx1, Stx2)

- Invasive plasmid antigen

- Hemolysin (HlyA)

Uropathogens

- P pili

- Dr fimbriae

Clinical Feature of E. coli

Gastroenteritis

- ETEC causes traveler’s diarrhea or infant diarrhea in infants. Pathogenesis involves plasmid-mediated, heat-stable (ST) and heat-labile (LT) enterotoxins that stimulate hypersecretion of fluids and electrolytes.

- EPEC causes infant diarrhea in developing countries. Pathogenesis involves plasmid-mediated A/E histopathology, with disruption of normal microvillus structure resulting in malabsorption and diarrhea.

- EAEC causes infant diarrhea in developing and probably developed countries along with traveler’s diarrhea. Pathogenesis involves plasmid-mediated aggregative adherence of rods (“stacked bricks”) with shortening of microvilli, mononuclear infiltration, and hemorrhage; decreased fluid absorption.

- STEC causes hemorrhagic colitis. STEC evolved from EPEC; A/E lesions with the destruction of intestinal microvilli, resulting in decreased absorption; pathology mediated by cytotoxic Shiga toxins (Stx1, Stx2), which disrupt protein synthesis

- EIEC causes disease which is rare in developing and developed countries. Pathogenesis involves plasmid-mediated invasion and destruction of epithelial cells lining the colon.

Urinary Tract Infection

- Most gram-negative rods that produce UTIs originate in the colon, contaminate the urethra, ascend into the bladder, and may migrate to the kidney or prostate.

- Although most strains of E. coli can produce UTIs, the disease is more common with certain specific serogroups.

- These bacteria are particularly virulent because of their ability to produce adhesins (primarily P pili, AAF/I, AAF/III, and Dr) that bind to cells lining the bladder and upper urinary tract (preventing the elimination of the bacteria in voided urine) and hemolysin HlyA that lyses erythrocytes and other cell types (leading to cytokine release and stimulation of an inflammatory response).

Sepsis

- When normal host defenses are inadequate, E coli may reach the bloodstream and cause sepsis.

- Newborns may be highly susceptible to E coli sepsis because they lack IgM antibodies.

- Sepsis may occur secondary to urinary tract infection.

Meningitis

- E coli and group B streptococci are the leading causes of meningitis in infants.

- Approximately 75% of E coli from meningitis cases have the K1 antigen.

- This antigen cross-reacts with the group B capsular polysaccharide of N meningitidis.

- The mechanism of virulence-associated with the K1 antigen is not understood.

Clinical Manifestations of E. coli

Gastroenteritis

- watery or bloody diarrhea

- vomiting

- cramps

- nausea

- low-grade fever

- dehydration

- abdominal cramps

The most common bacteria found to cause UTIs is Escherichia coli (E. coli). Other bacteria can cause UTI, but E. coli is the culprit about 90 percent of the time. The major manifestations of the infection include:

- A strong, persistent urge to urinate

- A burning sensation when urinating

- Pelvic pressure

- Lower abdomen discomfort

- Frequent, painful urination

- Blood in urine

Acute bacterial meningitis

- Newborns with E. coli meningitis present with fever and failure to thrive or abnormal neurologic signs.

- Other findings in neonates include jaundice, decreased feeding, periods of apnea, and listlessness.

- Patients younger than 1 month present with irritability, lethargy, vomiting, lack of appetite, and seizures.

Laboratory Diagnosis of E. coli

Urinary Tract Infection

- Most urine specimens are obtained from adult patients via the clean-catch midstream technique.

- Bacteriuria can be detected microscopically using Gram staining of uncentrifuged urine specimens, Gram staining of centrifuged specimens, or direct observation of bacteria in urine specimens.

- On staining, E coli appear as non-spore-forming, Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium

- Routine urine cultures should be plated using calibrated loops for the semi-quantitative method.

Note: The most commonly used criterion for defining significant bacteriuria is the presence of ⩾105 CFU per milliliter of urine. - The types of media used for routine cultures should be limited to blood agar and MacConkey’s agar.

- Urine cultures should be incubated overnight at 35°C–37°C in ambient air before being read.

Test/ Reactions

E. coli typically produces positive test results for indole, lysine decarboxylase, lactose, and mannitol fermentation and produces gas from glucose. An isolate from urine can be quickly identified as E. coli by its hemolysis on blood agar, typical colonial morphology with an iridescent “sheen” on differential media such as EMB agar, and a positive spot indole test result. More than 90% of E. coli isolates are positive for β-glucuronidase using the substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-glucuronide (MUG).

Gastroenteritis

- ETEC: commercial immunoassays available for detecting ST in clinical specimens and cultures; PCR assays used with clinical specimens.

- EPEC: Characteristic adherence to HEp-2 or HeLa cells; probes and amplification assays developed for the plasmid-encoded bundle-forming pili and gene targets on the “locus of enterocyte effacement” pathogenicity island.

- EAEC: Characteristic adherence to HEp-2 cells; DNA probe and amplification assays developed for conserved plasmid.

- STEC: Screen for O157: H7 with sorbitol MacConkey agar; confirm by serotyping; immunoassays (ELISA, latex agglutination) for detection of the Stx toxins in stool specimens and cultured bacteria; DNA amplification assays developed for Stx genes.

- EIEC: Sereny (guinea pig keratoconjunctivitis) test; plaque assay in HeLa cells; probes and amplification assays for genes regulating invasion (cannot discriminate between EIEC and Shigella).

Treatment of E. coli infections

- The sulfonamides, ampicillin, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides have marked antibacterial effects against the enterics, but variation in susceptibility is great, and laboratory tests for antibiotic susceptibility are essential.

- E. coli meningitis requires antibiotics, such as third-generation cephalosporins (eg, ceftriaxone).

- E. coli pneumonia requires respiratory support, adequate oxygenation, and antibiotics, such as third-generation cephalosporins or fluoroquinolones.

- In most cases of diarrheal disease, antibiotics are not prescribed. The best way to treat E coli infection is to drink plenty of fluids to avoid dehydration and to get as much rest as possible. However, patients should avoid dairy products because those products may induce temporary lactose intolerance, and therefore make diarrhea worse.

Prevention and Control of E. coli infections

- It is widely recommended that caution be observed in regard to food and drink in areas where environmental sanitation is poor and that early and brief treatment (eg, with ciprofloxacin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) be substituted for prophylaxis.

- Their control depends on handwashing, rigorous asepsis, sterilization of equipment, disinfection, restraint in intravenous therapy, and strict precautions in keeping the urinary tract sterile (ie, closed drainage).

References and Sources

- Ananthanarayan and Paniker. Textbook of Microbiology.

- Bailey and Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology. Part 3. Section 7. Chapter 22. Enterobacteriaceae, 323.

- Mackie and McCartney Practical Medical Microbiology. Section B. Bacteria and Related Organisms. Chapter 20. Escherichia, 361.

- Murray, P. R., Rosenthal, K. S., & Pfaller, M. A. (2013). Medical microbiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders

- Sastry A.S. & Bhat S.K. (2016). Essentials of Medical Microbiology. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers.

- Scaletsky, I. C., Fabbricotti, S. H., Carvalho, R. L., Nunes, C. R., Maranhão, H. S., Morais, M. B., & Fagundes-Neto, U. (2002). Diffusely adherent Escherichia coli as a cause of acute diarrhea in young children in Northeast Brazil: a case-control study. Journal of clinical microbiology, 40(2), 645-8.

- Subhash Chandra Parija. Textbook of Microbiology & Immunology.

- Topley and Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbial Infection. Bacteriology Volume 2. Part VI. Organisms and their biology. Chapter 36. Escherichia, 1360.

- http://academic.pgcc.edu/~kroberts/web/colony/colony.htm

- http://azcache.com/post/what-is-the-natural-habitat-of-ecoli-ehow-5710ee23db127b690d5132f7

- http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/s2008/moder_just/habitat.htm

- http://ecoliwiki.net/colipedia/index.php/Escherichia_coli

- http://hccfl.edu/media/870592/bacteria%20colony%20appearance%20morphology.doc

- http://mmbr.asm.org/content/62/1/110.full

- http://science.jrank.org/pages/2571/Escherichia-coli.html

- http://textbookofbacteriology.net/e.coli.html

- http://www.answers.com/Q/What_is_the_natural_habitat_of_E._coli

- http://www.bacteriainphotos.com/bacteria%20under%20microscope/staphylococcus%20and%20ecoli%20microscopy.html

- http://www.ehow.com/facts_5876351_natural-habitat-e_coli_.html

- http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Escherichia_coli.aspx

- http://www.hi-tm.com/1908/SECTION-2-D-1908.pdf

- http://www.microbiologyinpictures.com/escherichia%20coli.html

- http://www.microbiologyresearch.org/docserver/fulltext/micro/49/1/mic-49-1-165.pdf

- http://www.nos.org/media/documents/dmlt/Microbiology/Lesson-21.pdf

- http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/microbiologyescherichiacoli.html

- http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/lab-bio/res/psds-ftss/escherichia-coli-pa-eng.php

- http://www.questionstudy.com/biology/describe-the-structure-and-habitat-of-an-e-coli-bacteria.html

- http://www.vetbact.org/vetbact/?artid=68

- http://ymbiodelaramdescherichiacoli.weebly.com/habitat.html

- https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/38/8/1150/441696

- https://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/s2013/champa_hail/habitat.htm

- https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2180-13-22

- https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2180-13-22

- https://cmr.asm.org/content/11/1/142

- https://cmr.asm.org/content/27/4/823

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/217485-clinical

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escherichia_coli

- https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Escherichia_coli

- https://nios.ac.in/media/documents/dmlt/Microbiology/Lesson-21.pdf

- https://snowbio.wikispaces.com/E.+coli+(bacteria)

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/e-coli/symptoms-causes/syc-20372058

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5156508/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/019643999390012C

isn’t it facultative anaerobic bacteria?

Yes, it is a facultative anaerobic bacteria. Thanks for the correction. The page has been updated.

E. coli is a gamma hemolytic bacteria. The image provided fits gamma hemolysis, I am not sure why right underneath it is described as beta hemolysis.

Thank you so much.

Since E. coli can be both beta and gamma hemolytic, we have added both images. Thank you for the suggestion and correction.

Best,

Sagar