- Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) are a heterogeneous collection of strains characterized by their autoagglutination in a “stacked-brick” arrangement over the epithelium of the small intestine and, in some cases, the colon.

- EAEC strains are currently defined as E. coli strains that do not secrete enterotoxins LT or ST and that adhere to HEp-2 cells in an AA pattern.

- The prevalence of disease caused by EAEC is unclear because a single molecular marker for these bacteria has not been discovered.

- Genes encoding adhesins, toxins including Shiga toxin, and other virulence proteins are highly variable among EAEC.

- Outbreaks of gastroenteritis caused by EAEC have been reported in the United States, Europe, and Japan and are likely an important cause of childhood diarrhea in developed countries besides the developing countries.

- Enteroaggregative E coli (EAEC) has recently received increasing attention as an emerging enteric pathogen.

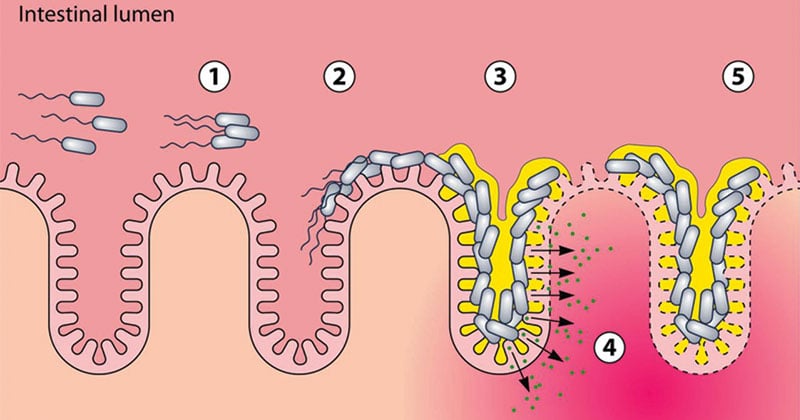

Figure: Stages of pathogenesis of EAEC. Numbers in circles show the progression of EAEC pathogenesis. (1) Agglutination of planktonic EAEC bacteria. (2) Adherence to the intestinal epithelium and colonization of the gut. (3) Formation of biofilm. (4) Release of bacterial toxins, inducing damage to the epithelium and increased secretion. (5) Establishment of additional biofilm. Source: DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00112-13

Interesting Science Videos

Disease Caused

These are one of the few bacteria associated with chronic diarrhea and growth retardation in children.

They typically exhibit plasmid-mediated aggregative adherence (“stacked bricks”) resulting in the shortening of microvilli, mononuclear infiltration, and hemorrhage; and decreased fluid absorption.

Risk Groups and Source of Infection

Contaminated food appears to be the main source of EAEC infection and has been implicated in several foodborne outbreaks of diarrhea.

Contamination of food and water plays a central role in transmission.

EAEC has been linked with persistent diarrhea in children living in areas where

- EAEC is endemic

- Individuals with human immunodeficiency virus infection and

- As a cause of diarrhea in travelers from industrialized countries visiting less-developed areas of the world.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of EAEC infection is not well understood. However, a three-stage model based on in vitro and animal is widely accepted.

- Stage I involves initial adherence to the intestinal mucosa and/or the mucus layer. AAF/I and AAF/II are the leading candidates for factors that may facilitate initial colonization.

- Aggregative adherence fimbriae I (AAF/I) is a flexible, bundle-forming fimbrial structure of 2 to 3 nm diameter.

- A second fimbria (designated AAF/II), is distinct morphologically and genetically from AAF/I, has now been identified.

- Stage II involves enhanced mucus production, apparently leading to deposition of a thick mucus-containing biofilm encrusted with EAEC. The blanket may promote persistent colonization and perhaps nutrient malabsorption.

- Stage III, suggested from histopathologic and molecular evidence, includes the elaboration of an EAEC cytotoxin which results in damage to intestinal cells. It is believed to produce EAST l toxin (entero-aggregative heat stable enterotoxin l).

- Characteristically, following adherence to the epithelium, cytokine release is stimulated, which results in neutrophil recruitment and progression to an inflammatory diarrhea.

It is tempting to speculate that malnourished hosts may be particularly impaired in their ability to repair this damage, leading to the persistent-diarrhea syndrome.

Clinical Features

Disease is characterized by:

- Watery secretory diarrhea, often with inflammatory cells

- Low Grade Fever

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Dehydration

- Abdominal pain

This process can be either acute or progress to a persistent diarrhea, particularly in children and HIV-infected patients.

Diagnosis

EAEC infection is diagnosed definitively by the isolation of E. coli from the stools of patients and the demonstration of the AA pattern in the HEp-2 assay.

HEp-2 assay. The HEp-2 assay remains the gold standard for detection of EAEC. Although variations in the AA pattern can be discerned, the presence of bacterial clusters in a stacked-brick configuration should be used to identify EAEC strains.

DNA probe. Several lines of evidence suggest that the large plasmids present in most EAEC strains have a high degree of DNA homology. The nucleotide sequence of the AA probe represents a cryptic open reading frame which is adjacent to the plasmid replicon. A PCR assay with primers derived from the AA probe sequence can be used for the detection of the desired sequence.

Other tests for EAEC.

- Test for EAEC probe-positive organisms displaying an unusual pellicle formation in Mueller-Hinton broth.

- Growing EAEC strains in polystyrene culture tubes or dishes at 37°C overnight without shaking, and checking the production of a bacterial film on the polystyrene surface which can be easily visualized with Giemsa stain.

Treatment

- Many EAEC infections are self-limited.

- Symptomatic infections are usually treated empirically because laboratory diagnosis is not routinely available. Patients with profuse diarrhea or vomiting should be rehydrated.

- Antibiotics to treat non-STEC diarrheagenic E. coli include fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin, macrolides such as azithromycin, and rifaximin.

- EAEC susceptibility varies by region. In most regions, EAEC strains are susceptible to the fluoroquinolones and rifaximin.

References

- Murray, P. R., Rosenthal, K. S., & Pfaller, M. A. (2013). Medical microbiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders

- Parija S.C. (2012). Textbook of Microbiology & Immunology.(2 ed.). India: Elsevier India.

- Sastry A.S. & Bhat S.K. (2016). Essentials of Medical Microbiology. New Delhi : Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers.

- https://cmr.asm.org/content/11/1/142

- https://www.amboss.com/us/knowledge/Diarrheagenic_E._coli

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7546449

- https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/22/7/15-2080_article

- https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/escherichia-coli-diarrheagenic

- https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/4/2/98-0212_article

- http://antimicrobe.org/h04c.files/history/E.%20Coli-Infect%20in%20Med%20-Cennimo%20et%20al%20article.pdf

- https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/202/4/503/2192058