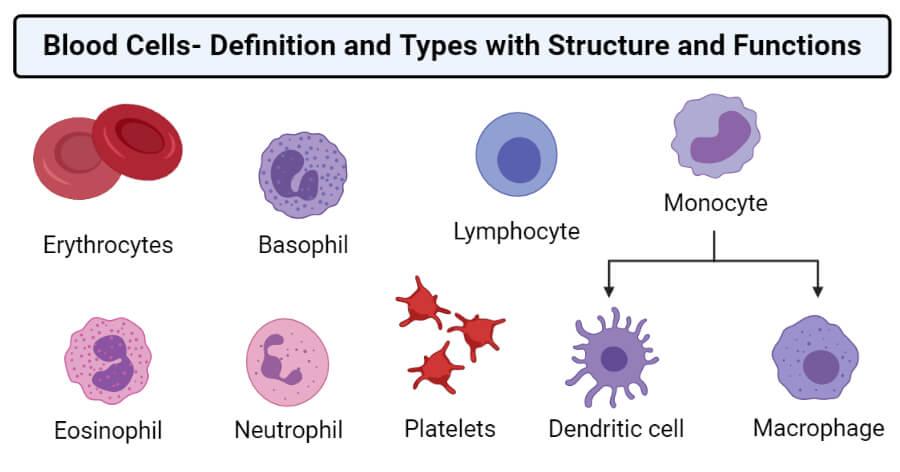

Blood cells, also known as hematocytes, hemocytes, or hematopoietic cells, are cells produced mostly in the blood and are synthesized primarily in the red bone marrow.

- Blood cells make up about 45% of the blood volume, while the rest (55%) is occupied by blood plasma.

- Blood contains three different types of blood cells, namely, red blood cell (erythrocytes), white blood cell (leukocytes), and platelets.

- In turn, there are three types of white blood cells—lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes—and three main types of granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils).

- These cells all come from the bone marrow where they develop as stem cells, followed by their maturation into one of the three types of blood cells.

- Blood cells are crucial for various functions of blood like transporting oxygen and other essentials, protecting against antigens, and restoring tissues in the body.

Types of Blood cells

Interesting Science Videos

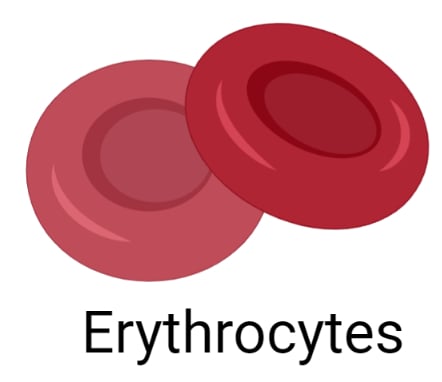

A. Red blood cells (RBC) or Erythrocytes

- Red blood cells (RBCs) or erythrocytes are blood cells with terminally differentiated structures lacking nuclei and are filled with the O2-carrying protein, hemoglobin.

- Erythrocytes are the functional component of blood involved in the transportation of gases and nutrients throughout the human body.

- The cells have unique shape and composition which allow for these specialized cells to carry out their essential functions.

- Because of the lack of a nucleus, erythrocytes cannot divide and thus need to be continually replaced by new cells synthesized in the red bone marrow.

- The lifespan of red blood cells is about 120 days, and the development of red blood cells from stem cells occurs in about seven days via the process of erythropoiesis.

Structure of Erythrocytes

- The mature human erythrocyte has a biconcave, discoid shape and is anucleated. They are approximately 7.5 μm in diameter, 2.6-μm thick at the rim, but only 0.75-μm thick in the center.

- The biconcave shape of the cell provides a large surface-to-volume ratio and facilitates gas exchange.

- The average concentration of erythrocytes in the blood is approximately 3.9-5.5 million per microliter (μL, or mm3) in women and 4.1-6.0 million/μL in men.

- Erythrocytes are quite flexible, which permits them to bend and adapt to the small diameters and irregular shape of the blood vessels.

- The plasmalemma of erythrocyte, because it is readily available for study, is the best-known membrane of any cell. The plasmalemma consists of about 40% lipid, 10% carbohydrate, and 50% protein.

- A phospholipid bilayer membrane supports the structure of the red blood cell, which is maintained by a network of proteins that make up the cytoskeleton.

- The cytoskeleton is composed of proteins like spectrin, actin, band 3, protein 4.1, and ankyrin, which allows for cellular structural integrity as well as malleability.

- The cytoplasm of erythrocytes lacks all organelles but is densely filled with hemoglobin, which allows the transportation of respiratory gases.

Functions of Erythrocytes

- RBCs transport oxygen from the lungs to the peripheral tissues to assist in metabolic processes such as ATP synthesis.

- The cells also collect the generated carbon dioxide from the periphery and return it to the lungs for elimination from the body.

B. White blood cells (WBC) or Leukocytes

- White blood cells (WBC) or leukocytes are a heterogeneous group of nucleated cells that are found in the blood that are primarily involved in the various activities related to immunity.

- The normal concentration of WBCs in human blood varies between 4000 and 10,000 per microliter.

- These cells play an essential role in phagocytosis and immunity and therefore in defense against infection.

- Leukocytes are separated into two major groups; granulocytes and agranulocytes, based on the density of their cytoplasmic granules.

1. Granulocytes

- Granulocytes are a group of white blood cells that are characterized by the presence of cytoplasmic granules.

- All granulocytes are differentiated cells with a life span of only a few days.

- The cell contains Golgi complexes and rough ER that are poorly developed, with few mitochondria mainly needed for glycolysis to meet their energy needs.

- Granulocytes are further divided into eosinophils, neutrophils, and basophils depending on their reaction to different dyes.

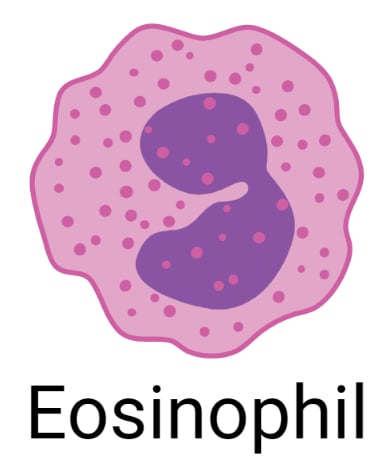

a. Eosinophils

- Eosinophils are granulocytes with a bilobed nucleus that can be differentiated from other leukocytes based on the presence of abundant large, acidophilic specific granules typically staining pink or red.

- Eosinophils are relatively less numerous than neutrophils, constituting only 1%-4% of total leukocytes.

- Ultrastructurally the eosinophilic specific granules are seen to be oval in shape, with flattened crystalloid cores containing major basic proteins.

- Eosinophils are particularly abundant in the connective tissue of the intestinal lining and at sites of chronic inflammation, such as lung tissues of asthma patients.

- Eosinophils also modulate inflammatory responses by releasing chemokines, cytokines, and lipid mediators, with an important role in the inflammatory response triggered by allergies.

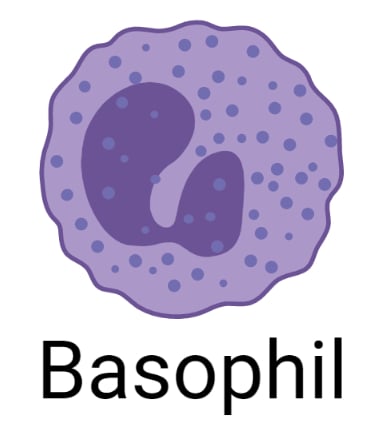

b. Basophils

- Basophils are blood cells in which the nucleus is divided into two irregular lobes, with specific cytoplasmic granules (0.5 μm in diameter) that typically stain purple with the basic dyes.

- The granules are fewer, larger, and more irregularly shaped than the granules of other granulocytes.

- Basophils are also 12-15 μm in diameter but make up less than 1% of circulating leukocytes and are therefore are difficult to find in normal blood smears.

- The strong basophilia of the granules is due to the presence of heparin and other sulfated GAGs.

- Basophilic granules also contain much histamine and various other mediators of inflammation, including platelet-activating factor, eosinophil chemotactic factor, and the enzyme phospholipase A.

- By migrating into connective tissues, basophils supplement the functions of mast cells as they have surface receptors for immunoglobulin E (IgE), and also secrete their granular components in response to certain antigens and allergens.

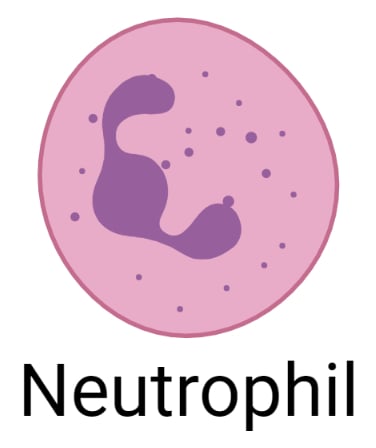

c. Neutrophils

- Neutrophils are small, fast, and active scavengers protect the body against bacterial invasion and remove dead cells and debris from damaged tissues.

- Neutrophils are characterized by nuclei that are characteristically complex, with up to six lobes connected by thin nuclear extension, and their granules are lysosomes containing enzymes to digest engulfed material.

- The lifespan of neutrophils is an average of 6–9 hours in the bloodstream, and their numbers rise very quickly in an area of damaged or infected tissue. Mature neutrophils constitute 50%-70% of circulating leukocytes.

- The neutrophils are attracted in large numbers to any area of infection by chemicals called chemotaxins, released by damaged cells.

- Neutrophils are highly motile so that they can squeeze through the capillary walls in the affected area by the process called diapedesis.

- Neutrophils are the first leukocytes to reach the sites of infection where they actively pursue bacterial cells using chemotaxis and remove the invaders or their debris by phagocytosis.

2. Agranulocytes

- Agranulocytes lack specific granules but do contain some azurophilic granules (lysosomes). The nucleus is spherical or indented but not lobulated.

- Leukocytes play an essential role in the constant defense against invading microorganisms and in the repair of injured tissues.

- Agranulocytes include the lymphocytes and monocytes, both of which crucial against antigens and pathogenic microorganisms.

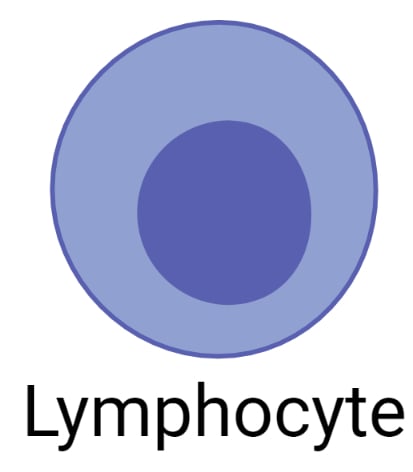

a. Lymphocytes

- Lymphocytes are round cells that contain a single, large round nucleus. There are two main classes of lymphocytic cells; the B cells that mature in the bone marrow, and the T cells that mature in the thymus gland.

- Lymphocytes are typically the smallest leukocytes and constitute approximately a third of these cells.

- Although generally small, circulating lymphocytes have a wider range of sizes than most leukocytes.

- Small, newly released lymphocytes have diameters similar to those of RBCs; medium and large lymphocytes (matured) are 9-18 μm in diameter.

- Some lymphocytes circulate in the blood, but most cells remain in tissues, including lymphatic tissues such as lymph nodes and the spleen.

- Lymphocytes are formed from pluripotent stem cells in the red bone marrow and from precursors in lymphoid tissue.

- Lymphocytes, once activated, are involved in different forms of immune reactions.

- The activated B cells, also known as plasma cells, produce highly specific antibodies that bind to the agent that triggered the immune response.

- T cells, called helper T cells, secrete chemicals that recruit other immune cells and help coordinate their attack.

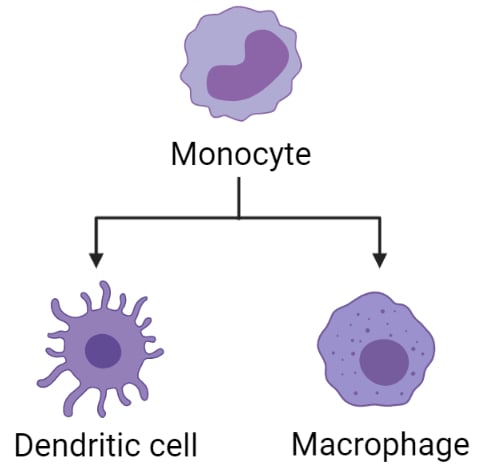

b. Monocytes

- Monocytes are agranulocytes that are the largest of all white blood cells, some of which also act as precursor cells of macrophages, osteoclasts, microglia, and other cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system in connective tissue.

- Circulating monocytes have diameters of 12-15 μm, but macrophages are often somewhat larger.

- The monocyte nucleus is large and usually distinctly indented or C-shaped, and the cells have dense chromatin.

- The cytoplasm of the monocyte is basophilic and contains many small lysosomal azurophilic granules.

- Mitochondria and small areas of rough ER are present, along with a Golgi apparatus involved in the formation of lysosomes.

- Monocytes are crucial for inflammation as they produce interleukin 1 that enhances both the activation of B cells and phagocytosis.

Read Also: 19 Differences between RBC and WBC (RBC vs WBC)

C. Platelets or Thrombocytes

- Blood platelets (or thrombocytes) are very small, 2-4 μm in diameter, non-nucleated, membrane-bound cells derived from the cytoplasm of megakaryocytes in the red bone marrow.

- Even though platelets like RBCs have no nucleus, their cytoplasm is packed with granules containing a variety of substances that promote blood clotting.

- The normal blood platelet count in humans is between 200 × 109/L and 350 × 109/L (200 000–350 000/mm3).

- The mechanism involved in the regulation of platelet numbers is not fully understood, but the hormone thrombopoietin from the liver is known to stimulate platelet production.

- The life span of platelets is between 8 and 11 days, and those not used in clotting are destroyed by macrophages, mainly in the spleen.

References and Sources

- Waugh A and Grant A. (2004) Anatomy and Physiology. Ninth Edition. Churchill Livingstone.

- Marieb EN and Hoehn K. (2013) Human Anatomy and Physiology. Ninth Edition. Pearson Education, Inc.

- Tortora GJ and Derrickson B (2017). Principles of Physiology and Anatomy. Fifteenth Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Dean L. Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2005. Chapter 1, Blood and the cells it contains.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2263/

- Barbalato L, Pillarisetty LS. Histology, Red Blood Cell. [Updated 2020 Jul 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539702/

- Blumenreich MS. The White Blood Cell and Differential Count. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 153.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK261/

- 5% – https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/28286/

- 3% – https://mybiblioteka.su/10-80714.html

- 2% – https://quizlet.com/49158006/33-lecture-connective-tissue-cells-derived-from-phsc-flash-cards/

- 2% – https://basicmedicalkey.com/blood-3/

- 2% – http://qu.edu.iq/el/mod/resource/view.php?id=60981

- 1% – https://www.slideshare.net/AbbasALRobaiyee1/blood-histology

- 1% – https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/erythropoiesis

- 1% – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/n/cm/A4532/

- 1% – https://www.britannica.com/science/red-blood-cell

- 1% – https://quizlet.com/517688514/kaplan-biology-chapter-8-flash-cards/

- 1% – https://quizlet.com/19936388/blood-cells-and-hematopoiesis-flash-cards/

- 1% – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blood_cell

- 1% – https://bloodcancer.org.uk/understanding-blood-cancer/blood-cells/

- 1% – http://www.tomhsiung.com/wordpress/tag/ecm/

there is very differ between cell like bonemaro cells

This article is very informative, but for one point–“Blood cells….are cells produced in the blood and are synthesized primarily in the red bone marrow.” As a patient advocate for sufferers of acute porphyria where hepatocytes are synthesized in the LIVER, I ask–can the same “typing” of cells be utilized?