According to FDA, yogurt is defined as the “food produced by culturing one or more of the optional dairy ingredients (cream, milk, partially skimmed milk, and skim milk) with a characterizing bacteria culture that contains the lactic acid-producing bacteria, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus”.

Milk fermentation is one of the oldest preservation methods adopted by human beings to preserve milk to extend its shelf life.

According to the Codex Alimentarius, yogurt is a good source of protein and other important nutrients.

Interesting Science Videos

What is Yogurt?

A yogurt is a fermented milk product that is made by combining two specific starter bacteria: Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus.

- In yogurt, some natural derivatives of milk are added, for example, whey concentrates, skim milk powder, caseinates, or creams, to create a gel structure caused by the coagulation of milk proteins, as well as the presence of lactic acid secreted by defined species of bacteria, which must be present or abundant at the time of consumption

- In addition to containing several essential nutrients, it also contains probiotics, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Sweeteners, fruits, flavors, rice, soy, and nuts can also be added to it to change the consistency and aroma according to taste

- In addition to its high digestibility and bioavailability, yogurt is considered a healthy food and can also be recommended to individuals with lactose intolerance, gastrointestinal disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel disease, as well as helping with weight loss and immunity.

History of Yogurt

- Around 5,000 years ago, yogurt was known to humans by nomadic people living in the Middle East.

- Throughout history, different civilizations have consumed it.

- It was named in the 8th century after the Turkish word “yogurmak,” which means to thicken, coagulate, or curdle.

- Fermented milk products are mentioned in Indian Ayurvedic scripts dating back to about 6000 BC.

- In 100 BC, the Greeks were the first to mention yogurt in written references.

- Around 1542, yogurt appeared in France. The king of France, Francis I, cured himself of chronic diarrhea by eating yogurt.

- Yogurt was believed to instill bravery in his soldiers by Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongol Empire.

- Bacillus bulgaricus was named in 1905 by Bulgarian medical student Stamen Grigorov, who studied in Geneva, Switzerland. It is a spherical and rod-shaped lactic acid bacterium found in Bulgarian yogurt.

- Yllia Metchnikoff, a Russian Nobel laureate from the Pasteur Institute in Paris, suggested in 1909 that lactobacilli in yogurt are linked to longevity among Bulgarian peasants.

- Isaac Carasso’s commercial production of yogurt in Barcelona, Spain, in 1919 was another major event in yogurt’s history.

- Heineman (1921) described an early method of making yogurt.

- In France, the first yogurt laboratory and factory opened in 1932; in the United States, the first laboratory and factory opened in 1941.

- In 1937, 1947, and 1963, flavored yogurts such as fruit yogurts and yogurts with fruit on the bottom were introduced.

- A few grocery and health food stores sold yogurt before the 1960s

- In the 1960s, Danone, a private company, industrialized yogurt and spread it throughout Europe.

- In 1984, the FAO/WHO defined yogurt as “coagulated milk obtained by lactic acid fermentation by Lactobacillus delbrueckii spp. Lactobacillus bulgaricus (Lb. bulgaricus) and Streptococcus thermophilus from milk.

- At present, various names are used to refer to yogurts such as Dahi or Dahee in India, Roba in Iraq, Fiili in Finland, zabadi (Egypt), mast (Iran), lebenraib (Saudi Arabia), laban (Iraq and Lebanon), roba (Sudan), iogurte (Brazil), cuajada (Spain), coalhada (Portugal), dovga (Azerbaijan), and matsoni (Georgia, Russia, and Japan).

- Today, many forms of yogurt can be found, including plain yogurt, fruit-flavored yogurt (including fruit-on-the-bottom and blended forms), whipped yogurt, granola-topped yogurt, drinkable yogurt, frozen yogurt, and Greek yogurt with varying fat contents (regular, low fat, and non-fat).

Ingredients of Yogurt

- Yogurt is a dairy product containing a variety of ingredients.

- The main ingredient is milk; sweeteners, stabilizers, fruits, flavors, and bacteria are also added.

- To make yogurt, the type of milk used depends on the desired fat content.

- Whole milk is used for full-fat or regular yogurt. Skim milk is used for fat-free yogurt, while partially skimmed milk is preferred for low-fat yogurt.

- The fat content of the yogurt mixture can be adjusted by adding cream or butterfat, while the solid content can be improved with skim milk powder and whey protein concentrate.

- Adding stabilizers to the mixture gives yogurt a smooth texture, whey separation is prevented, and ingredients are distributed evenly. Sweeteners are added to yogurt to enhance its flavor and aroma.

Manufacture of Yogurt

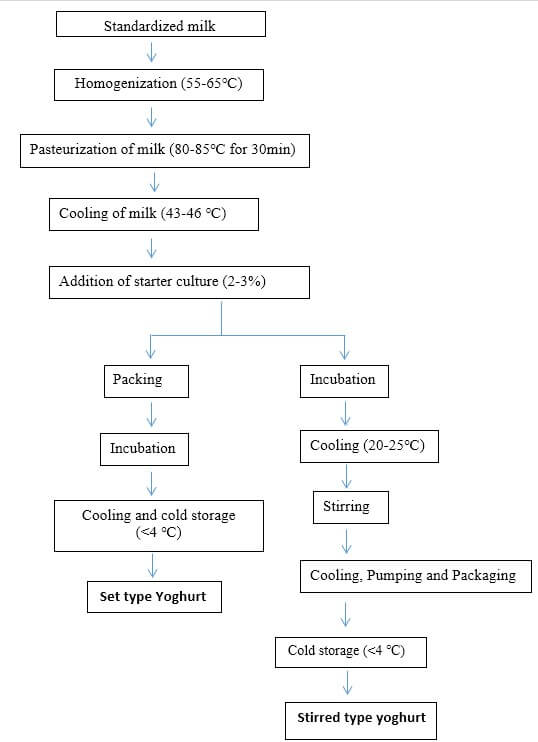

Yogurt is made through several steps, including blending, pasteurization, inoculation and fermentation, and cooling.

1. Pasteurization

- It is the first step in ensuring the product’s safety.

- During pasteurization, all pathogenic bacteria in the milk are killed, reducing the number of other organisms significantly and inactivating the enzymes in the milk.

- Generally, yogurt is pasteurized using a high-temperature short-time heat with a long holding time.

- Whey proteins are denatured by heat treatment and optimal conditions are created for yogurt culture growth.

- Denaturing whey proteins (80%–85%) improves their water binding capacity, which reduces free whey separation and improves yogurt consistency and viscosity.

2. Inoculation

- The yogurt mixture is cooled to 43-46℃ after pasteurization.

- Then 2-3% of yogurt starter culture bacteria are added to the mixture, usually Staphylococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus dulbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in a 1:1 ratio.

- A constant incubation temperature is maintained throughout the manufacturing process for yogurt.

- As the pH of yogurt approaches 5.0, microorganisms begin to operate, gradually dominating the fermentation process until the desired pH and acidity are reached.

- At 4℃, the process terminates, but the culture remains alive but has a limited ability to grow.

- In the fermentation process, lactose is converted into lactic acid by the lactic acid bacteria, which aids in the coagulation of milk proteins and the production of volatile compounds.

3. Cooling

- The final step is cooling, which consists of two phases.

- As the coagulum temperature drops rapidly below 10℃, fermentation is inhibited and yogurt with low viscosity is produced.

- In the second phase of cooling, the coagulum temperature decreases rapidly to less than 20˚C, and then the temperature of yogurt is lowered down to 5˚C (storage temperature) with increased viscosity.

- Upon manufacturing, set yogurts are directly transferred to cold storage for chilling, whereas stirred yogurts are first cooled down by agitation before being filled.

Microbiology of Yogurt

- The production of yogurt needs to begin with selecting high-quality milk that meets the necessary microbiological and chemical standards.

- Usually, milk is heated to a high temperature, between 85°C and 90°C, for a short time to sterilize it and denature the whey proteins.

- The purpose of this step is to ensure that any unwanted microorganisms are destroyed, which could spoil the yogurt.

- The milk is cooled to 43°C to 46°C after sterilization, which is an ideal growth temperature for Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus, which are commonly used in yogurt production.

- Lactose is fermented by the bacteria when added to milk as a mixed culture or separately.

- When bacteria consume lactose, they produce lactic acid, which drops the pH of milk and produces a solid gel-like texture by coagulating milk proteins.

- In yogurt, acidification is the key microbiological process responsible for giving it its characteristic thick and tangy texture.

- The fermentation process typically lasts four to eight hours, during which bacteria continue to consume lactose and produce lactic acid, further acidifying and thickening it.

- To ensure the fermentation process proceeds optimally and the final product meets the desired acidity and texture, the temperature and pH of the mixture are carefully controlled.

- Upon reaching the desired level of acidification and texture, the yogurt is cooled to stop fermentation and stabilize it.

- During this step, fruit, honey, or granola can be added as flavorings, sweeteners, or other ingredients.

- Yogurt is then packaged and distributed for consumption.

Types of Yogurt

Based on the physical nature

- Set yogurt

- Stirred yogurt

Based on Flavor

- plain/natural yogurt

- Flavored yogurt

Based on the production method

- Pasteurized and UHT yogurt

- Frozen yogurt

- Dried yogurt/yogurt powder

- Herbal yogurt

Health Benefits of Yogurt

- Yogurt containing active cultures may benefit gut health.

- Yogurt contains certain probiotic strains that may boost the immune system.

- High blood pressure and osteoporosis may be prevented by yogurt.

- Yogurt can help you recover post-workout as it is a high-protein food.

- The probiotics found in yogurt can improve digestion, metabolic health, and immunity, as well as delay or prevent cancer’s onset.

- Lactose-intolerant individuals can tolerate yogurt due to its natural protein content.

- The consumption of yogurt can result in fat burning and may protect against colon cancer.

- Yogurt may also lower the risk of vaginal infections and strengthen collagen in the skin.

- In addition to protecting against Helicobacter pylori, yogurt also strengthens the immune system.

- The health of your skin can also be improved by yogurt.

- Yogurt contains organic acids, bacteriocins, diacetyl, and hydrogen peroxide, which act as preservatives and prevent the growth of harmful bacteria.

Harmful effects of Yogurt

- Some people may have difficulty digesting lactose, which is found in yogurt. After consuming yogurt, lactose intolerant individuals may experience symptoms such as bloating, gas, and diarrhea.

- Proteins in yogurt can cause mild to severe allergic reactions in some people.

- Yogurts with added sugar can contribute to weight gain, diabetes, and other health problems.

- A poorly handled or stored yogurt can become contaminated with harmful bacteria. Foodborne illnesses can result from contaminated yogurt.

- Because yogurt is high in calcium, some medications, such as antibiotics, might be less effective if taken with yogurt.

References

- Adams, M. R., Moss, M. O., & McClure, P. J. (2008). Food microbiology. Royal Society of Chemistry.

- Aryana, Kayanush J., and Douglas W. Olson. 2017. “A 100-Year Review: Yogurt and Other Cultured Dairy Products.” Journal of Dairy Science 100(12):9987–10013. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-12981.

- Bhattarai, Nirmala, Mahalaxmi Pradhananga, and Shyam Kumar Mishra. 2016. “Effects of Various Stabilizers on Sensorial Quality of Yoghurt.” Sunsari Technical College Journal 2(1):7–12. doi: 10.3126/stcj.v2i1.14790.

- Chandan, Ramesh C. 2017. An Overview of Yogurt Production and Composition. Elsevier Inc.

- Chen, Chen, Shanshan Zhao, Guangfei Hao, Haiyan Yu, Huaixiang Tian, and Guozhong Zhao. 2017. “Role of Lactic Acid Bacteria on the Yogurt Flavour: A Review.” International Journal of Food Properties 20(1):S316–30. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2017.1295988.

- Fay, Daniel Lenox. 1967. Modern Indutrial Microbiology and Botechnology.

- Fisberg, Mauro, and Rachel Machado. 2015. “History of Yogurt and Current Patterns of Consumption.” Nutrition Reviews 73(July):4–7. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuv020.

- Gómez-Gallego, Carlos, Miguel Gueimonde, and Seppo Salminen. 2018. “The Role of Yogurt in Food-Based Dietary Guidelines.” Nutrition Reviews 76:29–39. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuy059.

- Húngaro, H. M., W. E. L. Peña, N. B. M. Silva, R. V. Carvalho, V. O. Alvarenga, and A. S. Sant’Ana. 2014. Food Microbiology.

- Kaur, Ramandeep, Gurpreet Kaur, Rima, Santosh Kumar Mishra, Harsh Panwar, K. K. Mishra, and Gurvir Singh Brar. 2017. “Yogurt: A Nature’s Wonder for Mankind.” International Journal of Fermented Foods 6(1):57. doi: 10.5958/2321-712x.2017.00006.0.

- McKinley, Michelle C. 2005. “The Nutrition and Health Benefits of Yoghurt.” International Journal of Dairy Technology 58(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0307.2005.00180.x.

- Nagaoka, Seiji. 2019. “Yogurt Production.” Methods in Molecular Biology 1887:45–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8907-2_5.

- Rul, Françoise. 2017. Yogurt: Microbiology, Organoleptic Properties and Probiotic Potential.

- Savaiano, Dennis A., and Robert W. Hutkins. 2021. “Yogurt, Cultured Fermented Milk, and Health: A Systematic Review.” Nutrition Reviews 79(5):599–614. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa013.

- Shwetnisha and Nongmaithem Mangalleima, Rajvir Singh, Malreddy Nikitha,. 2021. “The Product and the Manufacturing of Yoghurt.” International Journal for Modern Trends in Science and Technology 7(10):48–51. doi: 10.46501/ijmtst0710007.

- Soukoulis, C., P. Panagiotidis, R. Koureli, and C. Tzia. 2007. “Industrial Yogurt Manufacture: Monitoring of Fermentation Process and Improvement of Final Product Quality.” Journal of Dairy Science 90(6):2641–54. doi: 10.3168/jds.2006-802.

- Tamime, A. Y., and R. K. Robinson. 2007. “Microbiology of Yoghurt and Related Starter Cultures.” Tamime and Robinson’s Yoghurt 468–534. doi: 10.1533/9781845692612.468.

- Trachoo, Nathanon. 2002. “Yogurt : The Fermented Milk.” Journal of Science and Technology 24(4)(February):727–37.

- Weerathilake, W. A. D. V, D. M. D. Rasika, J. K. U. Ruwanmali, and M. A. D. D. Munasinghe. 2014. “The Evolution, Processing, Varieties and Health Benefits of Yogurt.” International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 4(1):2250–3153.