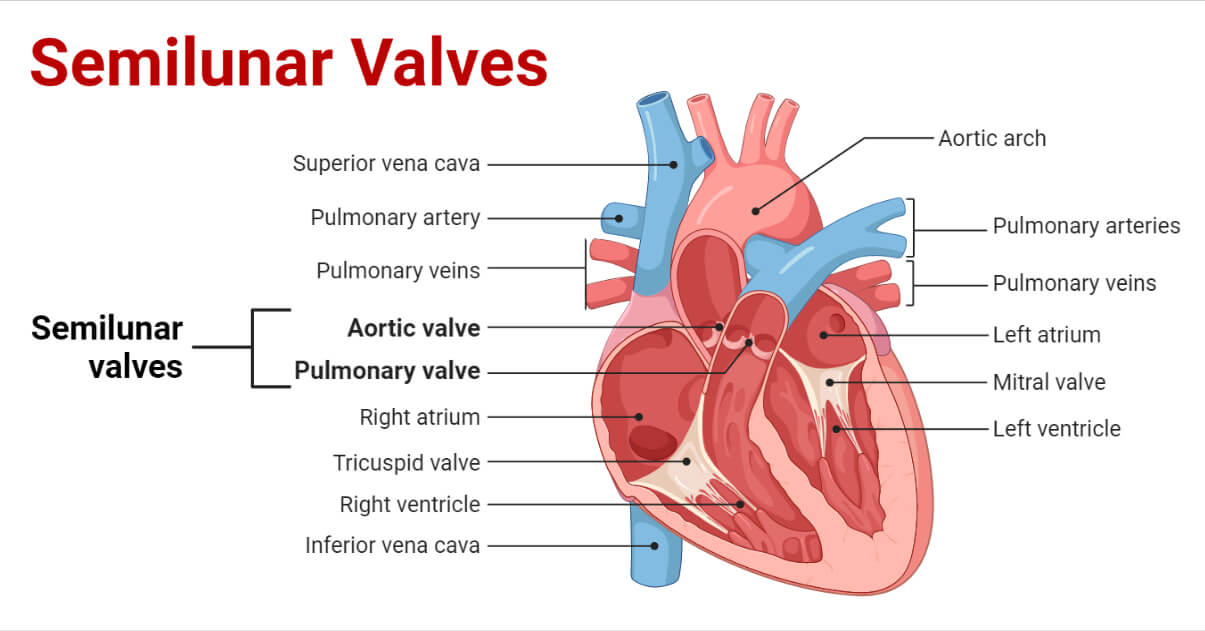

The heart valves are pivotal in maintaining the systolic and diastolic phases of the cardiac cycle.

There are two types of heart valves. They are:

- Atrioventricular valves

- Semilunar valves

Atrioventricular valves consist of the following:

- Bicuspid or Mitral valve

- Tricuspid valve

Semilunar valves consist of the following:

- Pulmonary valve

- Aortic valve

Interesting Science Videos

Embryology of Semilunar valves

- As the endocardial cushion develops in the outflow tract (OFT) of the primordial looping heart tube, the semilunar valves begin to form; this is the first indication of valvulogenesis.

- Later on, this fold in the endocardial cushion develops into a primitive heart valve containing cells that are highly proliferative valve progenitors.

- The valves are simple when remodeling and maturation are taking place.

- The primordial valve will develop into the semilunar valve’s narrow, fibrous cusp by lengthening and growing.

- During late gestation and shortly after birth, these leaflets will stratify into compartments made of highly organized collagen, proteoglycan, and elastin-rich extracellular matrix.

Anatomical Features of Semilunar valves

- A healthy semilunar valve comprises three valve leaflets, each connected to a specific sinus.

- These valves are between the main arteries that take blood away from the heart, the arterial trunks, and the ventricular outflow tracts.

- The semilunar valve leaflets do not need a tension apparatus to maintain competency, making this exquisite structure far simpler than the atrioventricular valves.

- When a valve is closed, its three leaflets appoint along fibrous zones called commissures, which are zones of apposition.

- A prominent fibrous nodule can be seen in the center of the valve, where all three leaflets cross.

- The margins of the valve leaflets are half-moon shaped when joined to the artery wall hence the name semilunar valve.

- The leaflet seats of the valves are often much lower than the areas where the commissures touch the artery wall, giving the valves a crown-like form.

Histological Features of Semilunar valves

- The distinctive histological features of the artery valves were first brought to light by Gross, whose account was later supported by Misfeld and colleagues.

- The semilunar valve’s leaflets each have a fibrous core or fibrosa, and their arterial and ventricular faces are lined by endothelial tissue that contains thin sheets of elastin.

- A thick collagenous layer of so-called fibrous “backbone” gives way to a much looser structure, known as a spongiosa, as it moves toward the ventricular portions of the leaflet cusps.

- The fibrous layer, composed of densely packed vertically oriented fibers, abruptly thickens and builds in the middle of the free edge to form the zone of apposition of the leaflets, creating a node termed Nodulus Arantii.

Types of Semilunar valves

1. Pulmonary Valve

- The semilunar valve that divides the right ventricle from the pulmonary trunk is the pulmonary valve.

- It has a diameter of about 20 mm.

- At the intersection of the pulmonary arterial trunk, the pulmonary valve’s annulus (ring-like connective tissue) anatomically delimits the right ventricular chamber.

- A crucial function in anchoring all the heart valves in the myocardium is played by the annulus and the cardiac fibrous skeleton. This structure connects the pulmonary valve to other heart valves.

- There are three cusps in the pulmonary valve: the anterior, left, and right cusps. These cusps are each divided from one another by a commissure.

- A muscle fold called the ventriculo-infundibular fold separates the tricuspid valve from the pulmonary valve.

- During the systolic phase of the cardiac cycle, the pulmonary valve opens, allowing the right ventricle to pump deoxygenated blood to the pulmonary circulation. It closes during the diastole phase, allowing the sufficient filling of the right ventricle.

2. Aortic Valve

- The aortic valve is situated in the middle of the heart between the mitral and tricuspid valves and is known as the “centerpiece” of the heart.

- It is often regarded as the most crucial cardiac valve in normal cardiac function.

- In the body surface area (BSA) range of 0.6 to 1.9 m2, the aortic valve size ranges from 12.2 mm to 21.2 mm, demonstrating a linear rise in diameter with increasing BSA.

- The aortic valve is a part of the aortic root. It consists of various structures, including the annulus, commissures, inter-leaflet triangles, sinus of Valsalva, sinotubular junction, and leaflets.

- The aortic valve is the connecting part between the left ventricle and the ascending aorta, which prevents blood backflow from the aorta.

- Blood will fill the cusps of the valve when the ventricle relaxes and tries to draw blood back into the ventricle from the aorta, which will cause the valve to close and make an audible sound.

- The aortic valve also helps to maintain a laminar flow in the circulatory system and adequate coronary perfusion.

Dysfunctioning of Semilunar valves

In general, dysfunctions of the semilunar valves are usually characterized by one of two symptoms:

- Failure of the valves to close successfully

- Failure of the valves to open successfully

Stenosis of the valve is described as the dysfunction of the valves during systole, i.e., the failure of the valve to open successfully. The size of the opening that permits blood to pass through the valve is reduced due to this condition, which makes the ventricles work harder to pump blood to the body or lungs.

Regurgitation is caused when blood from the arterial system is allowed to flow back into the ventricle during diastole when the ventricles are relaxing. This can overflow the ventricles and perhaps lead to chronic heart failure.

Clinical Imaging of Semilunar valves

To initially evaluate the condition of the semilunar valves, echocardiography can be the method of choice as it shows not only anatomical information but also functional details.

The pulmonary valve is typically observed from the parasternal long-axis view, while the aortic valve can be easily observed from the apical, parasternal long-axis, and suprasternal perspectives. This enables the echocardiographer to evaluate the following valve criteria:

- Size and shape of the annulus.

- The quantity and flexibility of the leaflets, particularly whether or not they move with restriction. Exclusion of thickening calcified cations, fusions along zones of apposition, and/or leaflet damage are also part of this examination.

- Whether there are any indications of localized abnormalities in the movements of the ventricles’ walls or their overall function is normal.

References

- Bateman, M. G., Quill, J. L., Hill, A. J., & Iaizzo, P. A. (2013). The anatomy and function of the semilunar valves. In Heart Valves (pp. 27-43). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Misfeld, M., & Sievers, H. H. (2007). Heart valve macro- and microstructure. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 362(1484), 1421–1436. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2125

- Rajendran, H. S., Seshayyan, S., Victor, A., & Rajapandian, G. (2013). Aortic valve annular dimension in Indian population. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR, 7(9), 1842–1845. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2013/5776.3329

- Sundjaja J. H., & Bordoni B. (2021). Anatomy, Thorax, Heart Pulmonic Valve. StatPearls Publishing LLC.

- Accessed from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547706/#!po=12.9630. Accessed on: 05.09.2022

- Vedantu. (2022). Semilunar Valve. Accessed from: https://www.vedantu.com/biology/semilunar-valve. Accessed on: 08.09.2022