Strongyloides stercoralis is a parasitic roundworm that causes strongyloidiasis. It is commonly called a threadworm in the US. It is the smallest nematode known to cause infection in humans. They are unique among nematode because it has both parasitic and free-living form.

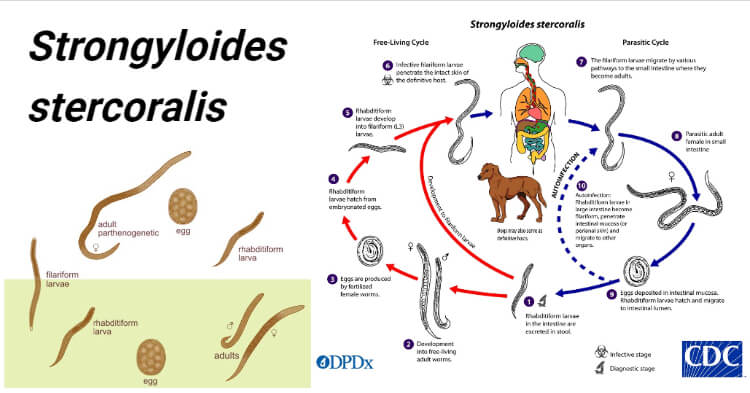

Image Source: The Australian Society for Parasitology and CDC.

Interesting Science Videos

History

- Strongyloides stercoralis was known as the “military worm”.

- It was first found by Normand in 1876 in the diarrheic feces of French soldiers in CochinChina and the name was coined by Stites and Hassall in 1902 where (strongylus—round; eidos—resembling; stercoralis—fecal).

- The life cycle and pathogenicity were described later during the early 1900s.

Distribution of Strongyloides stercoralis

- The infection of S. stercoralis is associated with fecal contamination of soil or water. Hence, its prevalence is higher in that area with poor sanitation and area associated with agricultural activity.

- It is found more frequently in socio-economically disadvantaged persons and in institutionalized populations.

- It has a cosmopolitan distribution in tropical and subtropical regions, but may also occur in temperate regions.

- It is common in Brazil, Columbia, and in the Far East—Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

- It is also endemic in the southeastern United States and southern Europe, although most cases in the US occur in immigrants refugees, travelers, and military veterans who have lived in endemic regions.

- Strongyloides infection is not limited to human hosts. Dogs and nonhuman primates are susceptible to infection and this may play an important role in transmission.

Habitat of Strongyloides stercoralis

- It exists in both a free-living form in the soil and as an intestinal parasite.

- The adult female worm is found in the small intestine (duodenum and jejunum) of a man whereas the free-living female worms multiply in the environment.

- Male worms are always free-living and thought to be non-parasitic.

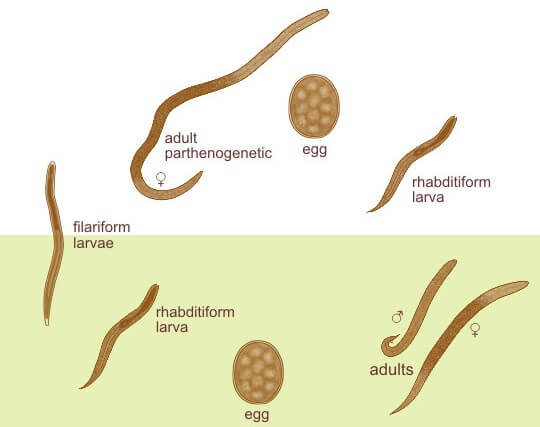

Morphology of Strongyloides stercoralis

Parasitic Female Worm

- The parasitic female worm is thin, semi-transparent, and colorless and lies embedded within the mucosal epithelium of the proximal small intestine.

- It measures about 2.5 mm long, and 0.05 mm wide, whereas the free-living female worm is smaller and thicker (1 mm × 80 μm).

- The anterior portion bears a mouth with three small lips.

- It has a cylindrical esophagus occupying the anterior one-third of the body, the intestines in the posterior two-thirds, and the mid ventrally situated anus.

- The posterior end is extremely pointed.

- The reproductive system contains paired uteri, vagina, and vulva. The paired uteri lead to the vulva situated at the junction of the middle and posterior thirds of the body.

- In the gravid female, the uteri contain thin-walled transparent ovoid eggs, 50 μm by 30 μm in size.

- The worm is ovoviviparous.

- A single female worm will produce up to 50 eggs per day.

- The individual worm has a lifespan of 3 or 4 months, but because it can cause autoinfection, the infection may persist for years.

* Its uterus intertwined, giving the appearance of a twisted thread, hence their common name is threadworm.

Parasitic male worm

- They are shorter and broader than females and measure about 0.6-1 mm in length and 40-50μm in width.

- They are not seen in human infection because they do not have penetrating power, therefore do not invade the intestinal wall.

- Parasitic males do not exist in infected humans.

- They possess two spicules at the posterior end, which penetrate the female during copulation.

Image Source: The Australian Society for Parasitology.

Eggs

- Eggs are conspicuous within the uterus of a gravid female.

- Each uterus contains 8–10 eggs arranged anteroposteriorly in a single row (Fig. 17.1).

- They are thin-shelled, transparent, and oval and measure 50–60 μm in length and 30– 35 μm in breadth

- Eggs of Strongyloides are ovoviviparous i.e they immediately hatch within the mucosa and emerge into the lumen of the small bowel as noninfectious rhabditiform larvae (first stage larvae), which are excreted in feces.

Larva

Rhabditiform Larva (L1 stage)

- This is the first stage of the larva which immediately hatch out of eggs in the small intestine.

- It is the most common form of parasite found in the feces.

- It is actively motile and measures 0.25 mm in length and 16µm in breadth.

- It has a short mouth, a relatively short muscular double bulb esophagus, and an inconspicuous genital primordium.

- The L1 larva migrates into the lumen of the intestine and passes down the gut to be released in feces, in a warm, humid environment, mature, and become free-living adult male and female worms.

- It is the diagnostic form found in human feces.

Filariform Larva (L3 stage)

- This is the third stage of the larva and infective stage.

- The L1 larva molts twice to become the L3 larva.

- It is long and slender and measures 0.55 mm in length.

- It has a short mouth with a long esophagus of uniform width and a notched tail.

- These infective L3 stages are long-lived and can persist in the environment until they encounter a suitable host

- They enter the human host through the skin like ancylostoma.

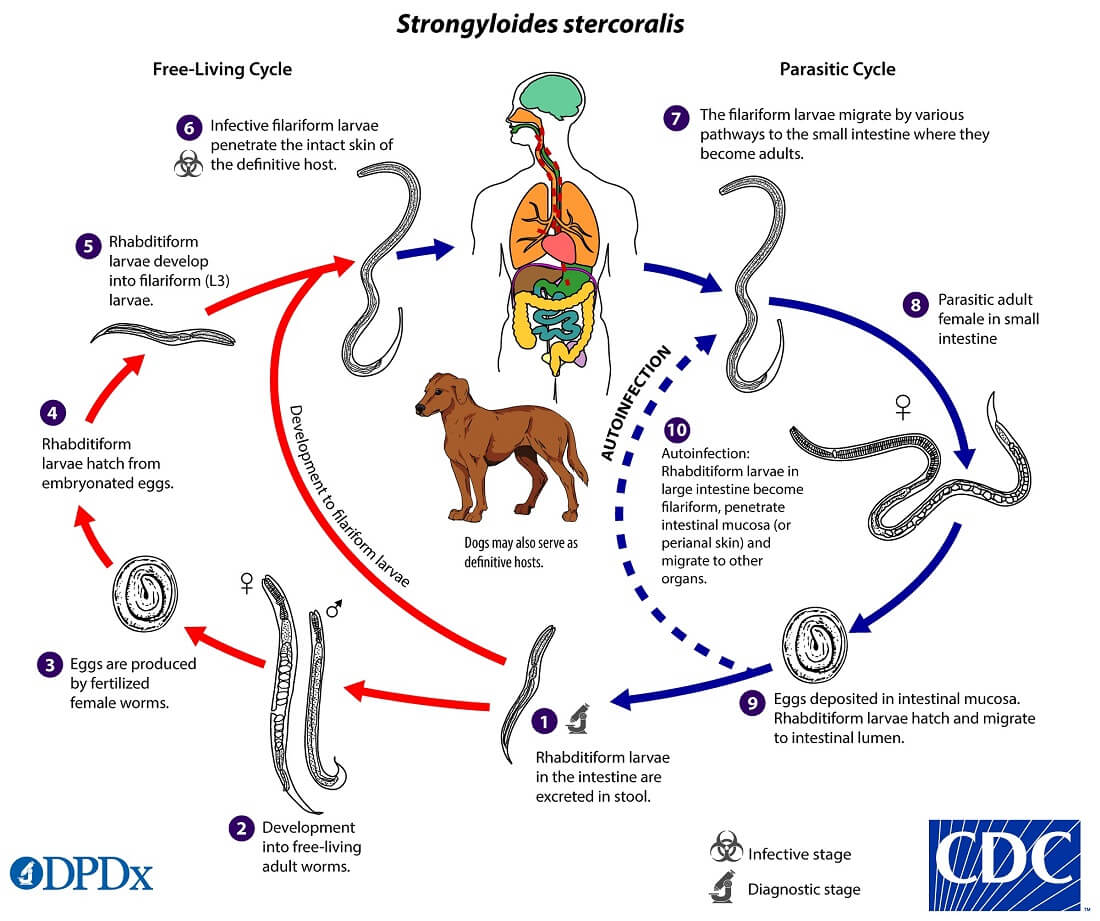

Life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis

Host: Involve single host (man)

Infective stage: Filariform larva (L3).

Image Source: CDC.

Mode of transmission

- The main source of infection is soil contaminated with human feces.

- Penetration of skin by the L3 larva (by walking barefoot). Larva releases hydrolytic enzymes that help in penetration.

- Autoinfection (internal autoinfection).

- By transplantation of organs such as kidneys to a new host.

- Though rare, other routes of transmission of the larva have been reported like in utero, transmammary routes, or zoonotic transmission.

The life cycle of S. stercoralis is complex because of the multiplicity of pathways through which it can develop. It is unique among human nematodes as it has a free-living soil cycle and a parasitic cycle, in which it can persist for long periods in soil by feeding on soil bacteria, passing through several generations.

1. Free-living soil cycle

- The embryonated eggs hatch within the mucosa and emerge into the lumen of the small bowel as noninfectious rhabditiform larvae

- The rhabditiform larvae are excreted in the stool of an infected definitive host in a warm, humid environment

- The larva passed with the feces may undergo two types of development in the soil

a. Direct Development

- The rhabditiform larva on reaching the soil moults twice to become the infective filariform larva(L3) within 3-4 days.

- The L3 larva acts as the infective form and infects man through the penetration of the skin.

b. Indirect Development

- The rhabditiform larva passed stool develops in the moist soil into free-living adult males and females within 24- 3o hours.

- The adult worms mate and the female produces embryonated eggs.

- The egg hatch out soon to release the next generation of rhabditiform larvae (L1) larvae which molt twice to became infective L3 filariform larvae.

- The filariform larvae penetrate intact skin leading to the parasitic phase of infection.

2. Parasitic cycle

- After penetrating the skin, the filariform larvae (L3) reach the right side of the heart, either through the lymphatics or the venules and then to the lungs via the pulmonary circulation.

- In the lungs, the larvae penetrate the alveoli, migrate up the tracheobronchial tree, and finally swallowing of sputum, they reach to Gastrointestinal tract.

- In the proximal small intestine, the larvae mol twice and become adult female worms, produce eggs via parthenogenesis (parasitic males do not exist)

- The adult female worms lodge in submucosal tissues of the small intestine.

- Egg production begins in 25-30 days after initially penetrating the skin.

- The rhabditiform larvae hatch out immediately and enter into the lumen of the bowel. They are excreted in the feces (free-living cycle) thus, the life cycle is repeated. or can cause autoinfection.

Autoinfection, Hyperinfection

- The more unusual feature of strongyloidiasis is the concept of autoinfection.

- The rhabditiform larvae can undergo transformation to filariform larvae in the distal colon or moist environment.

- This infectious filariform larva may penetrate colonic mucosa (internal autoinfection) or may penetrate the skin of the perianal area (external autoinfection) and “reinfect” the host.

- This process of autoinfection may be quite common and accounts for the persistence of this organism in the host for decades and may contribute to the development of hyperinfection.

- In the hyperinfection syndrome, the large numbers of rhabditiform larvae transform to filariform larvae, penetrate the colonic mucosa, and cause severe disease. This occurs in debilitated, malnourished, or immunosuppressed individuals.

- Glucocorticoid therapy is the main risk factor.

- Other risk factors include impaired gut motility, protein-calorie malnutrition, alcoholism, hypochlorhydria, lymphoma, organ transplantation, and lepromatous leprosy.

- Human T-cell lymphotropic virus Type 1 (HTLV-1) has also been associated with severe Strongyloides infection.

- The most severe form of hyperinfection syndrome is a disseminated infection in which larvae are found in other organs including the liver, kidney, and central nervous system.

Pathogenesis and Clinical features of Strongyloides stercoralis

- More than 50% of chronically infected people may be asymptomatic.

- Blood eosinophilia and larvae in stool being the only indications of infection.

- The clinical disease may have cutaneous, pulmonary, and intestinal manifestations.

Cutaneous Manifestations

- There may be dermatitis, with erythema and itching at the site of penetration of the filariform larva, particularly when large numbers of larvae enter the skin.

- In those sensitized by prior infection, there may be an allergic response.

- Pruritis and urticaria, particularly around the perianal skin and buttocks, are symptoms of chronic strongyloidiasis.

- The Migrating larvae may produce the pathognomonic serpiginous urticarial rash called larva currens (meaning ‘racing larvae’) that can progress as fast as 10 cm/hour. This is frequently seen on the buttocks, perineum, and thighs and may represent autoinfection.

Pulmonary Manifestations

- When the larva escapes from the pulmonary capillaries into the alveoli, small hemorrhages may occur in the alveoli and

bronchioles. - Pulmonary symptoms such as cough, wheezing, or shortness of breath may develop as well as fleeting pulmonary infiltrates and eosinophilia.

- Bronchopneumonia may be present, which may progress to chronic bronchitis and asthmatic symptoms in some patients.

- Larva of Strongyloides may be found in the sputum of these patients.

Intestinal Manifestations

- With the development of gastrointestinal involvement, there may be epigastric discomfort suggestive of peptic ulcer disease,

bloating, nausea and diarrhea. - Other manifestations are protein-losing enteropathy and paralytic ileus.

Complication

- Rarely, more severe infections have been associated with malabsorption and protein-calorie malnutrition.

- In many chronically infected individuals, symptoms resolve with the appearance of larvae in the stool, although most have persistent eosinophilia.

- Hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated strongyloidiasis are the important complications

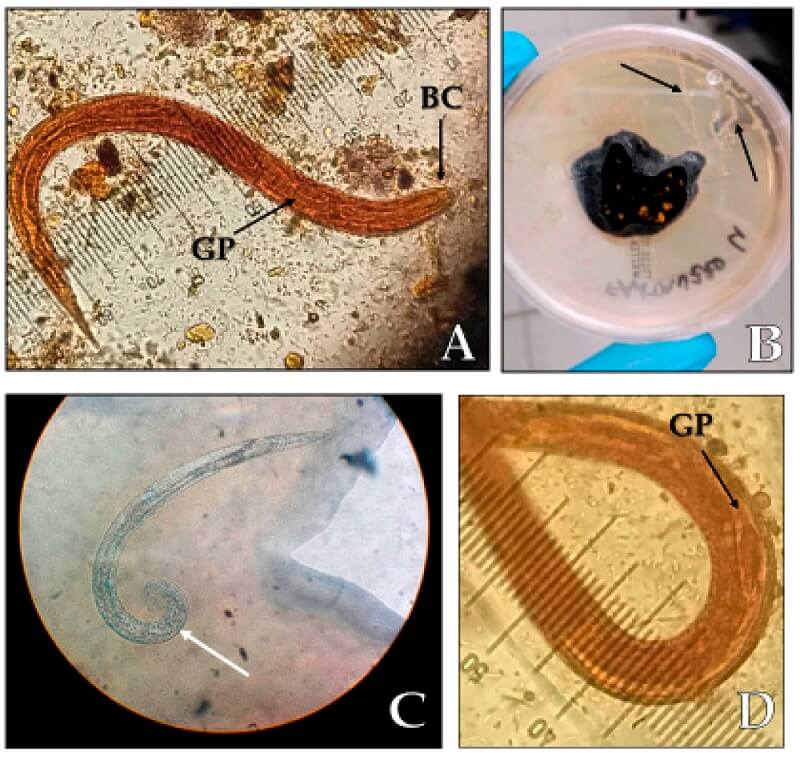

Laboratory diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis

Specimen: Stool, urine, and sputum

1. Microscopy

- Direct wet mount of stool and Concentration methods of stool examination is an important method for the demonstration of rhabditiform larva in freshly passed stools.

- The larvae found in the stool have to be differentiated from larvae hatched from hookworm eggs. They are distinguished by their shorter buccal cavity, notched tail, and esophagus present in one-half of the body.

- Stool examination is less sensitive (30%)due to the irregular and low output of larvae.

- Sometimes duodenal aspirate can be collected by enterotest and examined for the presence of larva.

- Disseminated strongyloidiasis can be readily diagnosed in sputum, other body fluids, and tissues which typically contain high numbers of filariform larvae.

Figure: (A) Strongyloides stercoralis rhabditoid larvae L1 (length 250 µm, magnification 40×), BC: buccal cavity, GP: germinal primordium; (B) migration paths of the larvae (black arrows) on an agar plate culture; (C) S. stercoralis adult male with spicule (white arrow); (D) germinal primordium. Image Source: Letizia Ottino et al. 2020.

2. Stool culture

- Stool culture is used when the larvae are scanty in the stool

- Culture techniques used—Harada Mori filter paper tube method, Petri dish (slant culture) technique, Baermann funnel technique, Agar plate culture, and Charcoal culture method.

- The larvae develop into free-living forms and multiply in charcoal cultures set up with stools.

- A large number of free-living larvae and adult worms can be seen after 7–10 days.

- The agar plate method was found to be 96% sensitive in determining the presence of Strongyloides.

3. Serology

- Serological tests have been described, using Strongyloides or filarial antigens.

- Complement fixation, indirect hemagglutination, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) have been reported.

- ELISA has a sensitivity of 95 % and should be used when microscopic examinations are negative but Specificity is less as a result

of cross-reactivity with other helminth infections.

4. Imaging

- Radiological appearances in intestinal and pulmonary infection are said to be characteristic and helpful in diagnosis.

5. Molecular diagnosis

- A real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect Strongyloides DNA in fecal samples has been developed and it has achieved 100% specificity and high sensitivity.

6. Others

- Peripheral eosinophilia (>500/cumL of blood) is a constant finding. However, in severe hyperinfection, eosinophilia may sometimes be absent.

- Total serum immunoglobulin (Ig)E antibody level is elevated in more than half of the patients

Treatments of Strongyloides stercoralis infections

For Acute and chronic strongyloidiasis

- Ivermectin, in a single dose, 200 µg/kg orally for 1-2 days. (Source: CDC)

- Albendazole, 400 mg orally two times a day for 7 days. (Source: CDC)

Hyperinfection syndrome/Disseminated strongyloidiasis

- Ivermectin, 200 µg/kg per day orally until stool and/or sputum exams are negative for 2 weeks. (Source: CDC)

Prophylaxis of Strongyloides stercoralis

- Prevention of contamination of soil with feces.

- Sanitary disposal of feces.

- Avoiding contact with infective soil and contaminated surface waters.

- Treatment of all infected cases.

References

- Stephen Gillespie (Editor) and Richard D. Pearson (Editor). 2001. Principles and Practice of Clinical Parasitology. Wiley.

- Abhay R. Satoskar. 2009. Medical Parasitology. 1st edition. CRC Press.

- Sougata Ghosh. 2017. Paniker’s Textbook of Medical Parasitology. 8th edition. Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub.

- Ottino L, Buonfrate D, Paradies P, Bisoffi Z, Antonelli A, Rossolini GM, Gabrielli S, Bartoloni A, Zammarchi L. Autochthonous Human and Canine Strongyloides stercoralis Infection in Europe: Report of a Human Case in An Italian Teen and Systematic Review of the Literature. Pathogens. 2020; 9(6):439. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9060439.

Sources

- https://www.onlinebiologynotes.com/strongyloides-stercoralis-morphology-life-cycle-pathogenesisdiseases-diagnosis-and-treatment/- 10%

- https://parasiticinfection.wordpress.com/2020/12/08/example-post-3/- 6%

- https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/strongyloidiasis/index.html– 3%

- http://wormbook.org/chapters/www_genomesStrongyloides/genomesStrongyloides.html- 2%

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strongyloides_stercoralis- 2%

- https://europepmc.org/article/MED/20733481- 1%

- https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0001044- 1%

- https://web.stanford.edu/group/parasites/ParaSites2003/strongyloides/lifecyclecontent.html- 1%

- https://labweeks.com/strongyloides-stercoralis/- 1%

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0580951719300285- <1%

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/parasitology/article/accuracy-of-realtime-polymerase-chain-reaction-to-detect-schistosoma-mansoni-infected-individuals-from-an-endemic-area-with-low-parasite-loads/30D48613B5707CE815BC6374E1AD6611- <1%

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/tiabendazole- <1%

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(20)30328-5/fulltext- <1%

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1235977/- <1%

Thanks I wanna appreciate for the good work done

Reading your recommendations re treatment of Strongyloidiasis and surprised by the dosage of 200mg/kg weight of affected person. So you are suggesting using 12,000mg of Ivermectin for a 60kg patient? Seems like there might be an error there…can you confirm the recommendation for me? Thank you in advance.

Hello Sav,

Thank you so much for the correction. There was a typing mistake, and now it has been updated according to the recommendation of the CDC.