Koch’s postulate forms the very basis of the pathogenic microbiology. The causality of almost all infectious diseases is based on the postulate and theories developed by Robert Koch, who is rightly called the “father of pathogenic microbiology,” and his contemporaries. Developed in the late 19th century, it has stood the test of time.

Interesting Science Videos

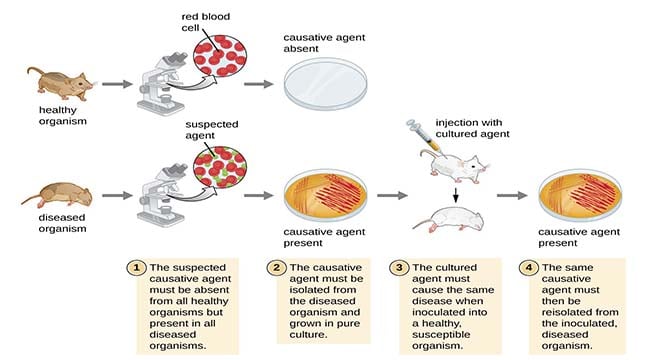

The postulate can be summarized as follows:

- A microbe suspected as the causal agent of a particular disease must be found in all subjects suffering from a similar disease but must be absent in clinical specimens from healthy individuals.

- The suspected microorganism can be isolated from the diseased individual and grown in pure culture.

- When this isolated suspect microbe is injected into healthy, susceptible animals (some human volunteers were also reportedly used by Robert Koch), signs and symptoms of a disease similar to the disease under investigation must develop in the infected animal.

- The microbe cultured from the infected animal must be morphologically and physiologically identical to the strain initially isolated from the patient (in point 1).

However, Koch’s postulates have their limitations and so may not always be the last word.

They may not hold if:

- The particular bacteria (such as the one that causes leprosy) cannot be “grown in pure culture” in the laboratory.

- There is no animal model of infection with that particular bacteria.

Harmless bacteria may cause disease if:

- It has acquired extra virulence factors making it pathogenic.

- It gains access to deep tissues via trauma, surgery, an IV line, etc.

- It infects an immunocompromised patient.

- Not all people infected by a bacteria may develop a disease-subclinical infection is usually more common than clinically obvious infection.

Despite such limitations, Koch’s postulates are still a useful benchmark in judging whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between a bacteria (or any other type of microorganism) and clinical disease.

Here are Koch’s postulates for the 21st century as suggested by Fredricks and Relman:

- A nucleic acid sequence belonging to a putative pathogen should be present in most cases of an infectious disease. Microbial nucleic acids should be found preferentially in those organs or gross anatomic sites known to be diseased, and not in those organs that lack pathology.

- Fewer, or no, copy numbers of pathogen-associated nucleic acid sequences should occur in hosts or tissues without the disease.

- With the resolution of disease, the copy number of pathogen-associated nucleic acid sequences should decrease or become undetectable. With clinical relapse, the opposite should occur.

- When sequence detection predates disease or sequence copy number correlates with severity of disease or pathology, the sequence-disease association is more likely to be a causal relationship.

- The nature of the microorganism inferred from the available sequence should be consistent with the known biological characteristics of that group of organisms.

- Tissue-sequence correlates should be sought at the cellular level: efforts should be made to demonstrate specific in situ hybridization of microbial sequence to areas of tissue pathology and to visible microorganisms or to areas where microorganisms are presumed to be located.

- These sequence-based forms of evidence for microbial causation should be reproducible.

Thanks for this. Wasn’t aware of the limitations but now am well-off

There is no dose assigned to a pathogen affecting a species of animal or plant. Lethal dose vs Infective dose.

This iz really informative! Thanks!