Nitrogen assimilation is a vital process by which inorganic nitrogen, such as nitrate and ammonium, is converted into usable organic forms, including amino acids, nucleotides, and proteins.

These are important for plant and microbial growth and development. This conversion enables organisms to integrate nitrogen into cellular compounds, which helps in metabolism, structural roles, and the synthesis of genetic material.

Main sources of Nitrogen

Different inorganic and organic sources of nitrogen are as follows-

Nitrate (NO₃⁻) – It is the most general form taken up by plants from the soil.

Ammonium (NH₄⁺) – It is assimilated directly into amino acids and is used during low-oxygen conditions.

Nitrite (NO₂⁻) – It is an intermediate form that is generally toxic, and to reduce its toxicity, it is reduced to ammonium.

Urea and other organic forms- It is generally used by microbes and, to a lesser degree, by plants.

Atmospheric Nitrogen (N₂) – It is used solely by nitrogen-fixing bacteria during the process of nitrogen fixation.

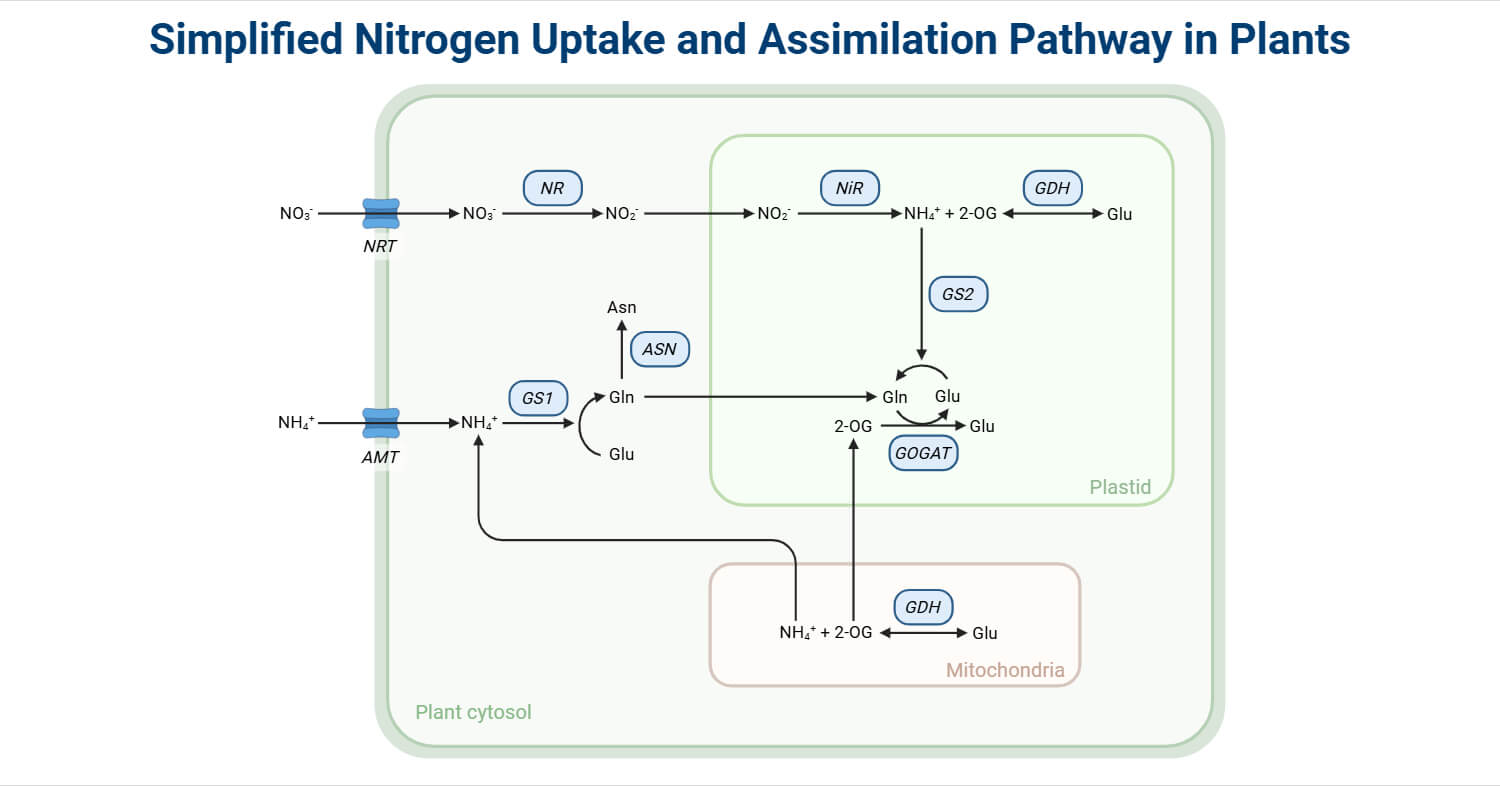

Nitrate uptake and reduction in plants

The major source of nitrogen for plants is nitrate. It is controlled by high and low-affinity nitrate transporters (NRTs), which are present in the root plasma membrane that helping in adjusting nitrogen concentrations.

Nitrate is delivered to the cytoplasm with the help of these transporters, and a series of enzymatic reductions is now initiated in order to assimilate nitrogen in different biological forms.

The initial and the limiting step of this process is catalysed by the enzyme Nitrate Reductase (NR), which converts nitrate to nitrite (NO₂⁻).

The reaction is as follows-

NO₃⁻ + NAD(P)H → NO₂⁻ + NAD(P)⁺ + H₂O

The efficient activity of nitrate reductase is significant not just for nitrogen uptake but also for redox balance and regulation of nitrogen-carbon interactions within the plant. Loss of function in nitrate reductase can result in nitrate accumulation, stunted growth, and decreased nitrogen-use efficiency. Thus, comprehension of the regulation and activity of this enzyme has general importance to agricultural productivity and environmental sustainability, especially in the development of strategies to decrease nitrogen fertilizer applications without diminishing crop yield.

Nitrate reductase

This enzyme is a homodimeric flavoprotein present in the cytosol, which has various cofactors required for its functioning, such as Molybdenum (Mo), Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD), and Heme-iron (Cytochrome b5). These cofactors are involved in the stepwise transfer of electrons from NADH or NADPH (isoform-dependent) to nitrate, which leads to the two-electron reduction of nitrate to nitrite. The reaction can be summarized as:

The enzymatic activity of NR is regulated by processes such as transcription and translation based on environmental conditions such as light, availability of carbon source, and endogenous N2 status.

During transcription, the genes for NR are activated by nitrate itself as a signal molecule, and then during translation, these genes form the enzyme. After the translation process, the enzyme is controlled by Phosphorylation and binding of a specific protein, which results in inactivation of enzymatic activity under stressful and dark conditions.

Nitrite Reductase

After the reduction of Nitrate into Nitrite by nitrite reductase in the cytosol, the next step is the reduction of nitrite to ammonium, which takes place in the non-photosynthetic region of chloroplasts. Nitrite is a potentially poisonous intermediate, and its quick reduction to ammonium is critical to avoid cell damage and preserve metabolic equilibrium. The reaction is as follows-

NO₂⁻ + 6Fd(reduced) + 8H⁺ → NH₄⁺ + 6Fd(oxidized) + 2H₂O

Nitrite Reductase (NiR)- It is a ferrodoxin-dependent iron-sulphur enzyme in plants. The enzyme has a siroheme cofactor and a 4Fe-4S cluster as its electron transfer centers, which are important for the transfer of electrons needed for reduction.

The activity of NiR is regulated by light, nitrate concentration, carbon source, and the plant’s nitrogen requirement. To create a balance and efficient way for nitrogen transfer from inorganic to biological form, coordination between NR and NiR enzymes is crucial.

The resultant ammonium formed is utilised immediately for amino acid synthesis through the GS-GOGAT cycle.

GS-GOGAT Cycle

The Glutamine Synthase-Glutamate Synthase Pathway is the main pathway by which ammonium is integrated into organic molecules in plants and micro-organisms. As ammonium is toxic, its rapid incorporation into non-toxic organic forms, i.e., amino acid, is crucial for metabolic homeostasis and nitrogen metabolism.

In the initial step of the cycle, glutamine synthetase (GS) catalyzes the ATP-dependent amination of glutamate to glutamine:

Glutamate + NH₄⁺ + ATP → Glutamine + ADP + Pi

Then glutamine is used as the nitrogen donor in the second reaction, catalyzed by glutamate synthase (GOGAT), which transfers the amide group from glutamine to 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) to yield two molecules of glutamate:

Glutamine + 2-oxoglutarate + NAD(P)H → 2 Glutamate + NAD(P)⁺

One of the glutamate molecules produced can be recycled into the cycle, and the other is made available for the biosynthesis of other amino acids, nucleotides, and nitrogenous compounds. The cycle effectively integrates inorganic nitrogen into organic forms, closely coupling nitrogen and carbon metabolism, particularly through 2-oxoglutarate, a central intermediate in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle.

The GS-GOGAT system is tightly controlled by internal nitrogen concentration, availability of carbon, light, and developmental state.

Alternate ammonia assimilation pathways

The GS-GOGAT cycle is the major pathway of ammonium assimilation; other pathways, like the Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) pathway, are also significant under certain physiological or stressful conditions.

Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) catalyzes the reversible reductive amination of 2-oxoglutarate to glutamate with NADH or NADPH as an electron donor:

NH₄⁺ + 2-oxoglutarate + NAD(P)H ↔ Glutamate + NAD(P)⁺ + H₂O

This process is energetically advantageous and does not demand ATP; thus, under energy-starved conditions, it is effective. Nevertheless, GDH possesses lower ammonium affinity than GS and, under standard physiological conditions, when ammonium levels are low, its activity is restricted.

Other alternative pathways and enzymes have been found in some organisms, for example, asparagine synthetase, which adds nitrogen to asparagine, an important plant nitrogen storage and transport molecule. Novel ammonia-assimilation enzymes are found in certain cyanobacteria and bacteria that assist in the incorporation of nitrogen under certain environmental conditions.

Though these alternative pathways are not the main route for nitrogen assimilation, they confer metabolic flexibility, particularly when plants or microbes encounter environmental fluctuations, stress, or nutrient imbalances.

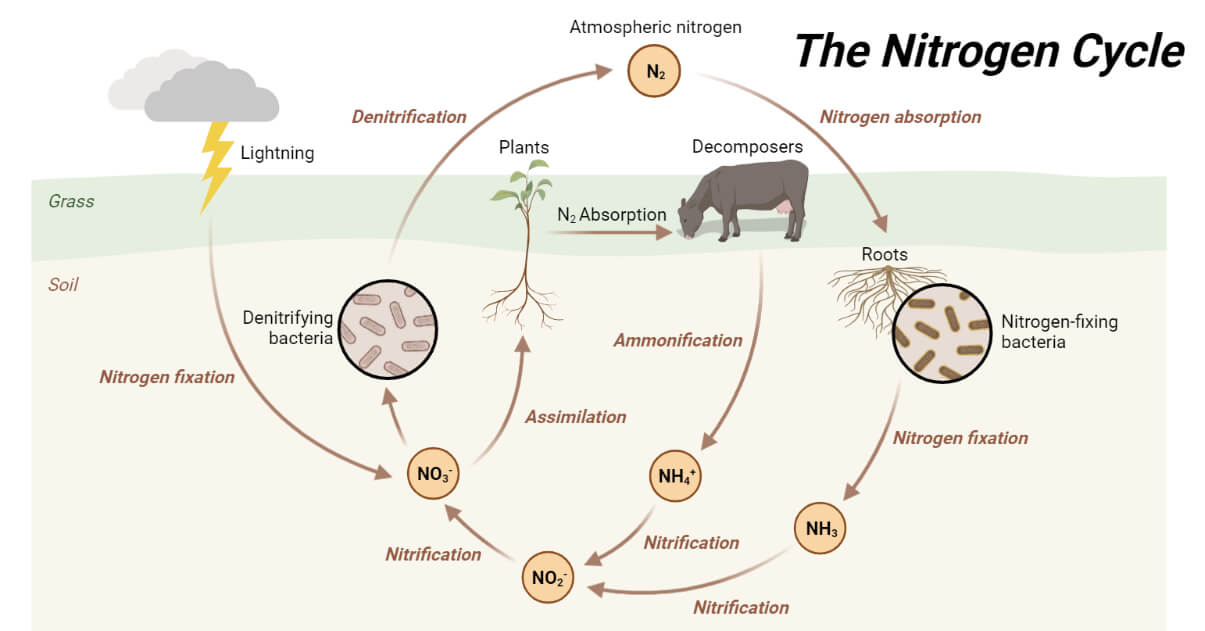

Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation

It is the beneficial association between leguminous plants and nitrogen-fixing bacteria such as Rhizobium. The nitrogen-fixing bacteria infect the root nodules of host plants and reduce atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) to ammonia (NH₃) with the help of the Nitrogenase enzyme. The fixed ammonia is then released into plant cells, where it is directly assimilated through the GS-GOGAT pathway to form glutamine and glutamate.

This symbiotic relationship improves plant nitrogen assimilation and decreases reliance on soil nitrogen or artificial sources. The plant, in turn, provides a food source and a shielded habitat for bacteria. This procedure greatly enriches soil fertility and is a foundation of sustainable agriculture.

Nitrogen assimilation in soil bacteria and Cyanobacteria

Soil bacteria and Cyanobacteria are essential agents of nitrogen assimilation based on their capacity to fix and efficiently assimilate nitrogen.

Soil bacteria such as Azotobacter, Bacillus, and Pseudomonas also assimilate ammonium through similar mechanisms and are involved in the nitrogen cycle by nitrification, denitrification, and mineralization.

Cyanobacteria such as Anabaena and Nostoc have specialized cells known as heterocysts that perform nitrogen fixation in anaerobic conditions. The ammonia formed is assimilated through the GS-GOGAT cycle, producing the necessary amino acids.

These microorganisms are responsible for keeping nitrogen available in ecosystems, particularly in poor or degraded soils.

Gene control of nitrogen assimilation enzymes

The regulation of nitrogen assimilation enzymes is tightly controlled and dynamic, which ensures that organisms are able to effectively sense, respond to, and adapt to changing nitrogen levels in their environment.

It is crucial in maintaining nitrogen homeostasis and maximizing nitrogen use for growth and development.

In microbes and plants, expression of major nitrogen assimilation genes like those that encode nitrate reductase (NR), nitrite reductase (NiR), glutamine synthetase (GS), and glutamate synthase (GOGAT) is highly regulated at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational levels.

Plant nitrogen assimilation genes tend to be induced with the availability of nitrate or ammonium from the outside. Nitrate is both a signaling molecule and a nutrient that evokes expression of nitrate assimilation genes by nitrate-responsive elements (NREs) in promoters. Among the essential regulators is the NIN-like protein (NLP) group of transcription factors. An example is NLP7 in Arabidopsis, which is a central integrator of nitrate signaling and regulates downstream genes NIA1 and NIA2 (encoding nitrate reductase enzymes) and NIR (coding for nitrite reductase). Moreover, light and carbon status modulate gene expression, connecting nitrogen assimilation with photosynthetic activity and energy availability.

Regulation of nitrogen assimilation in cyanobacteria and soil bacteria is mainly directed by regulators like NtcA, a transcriptional activator that is responsive to intracellular nitrogen status, mainly 2-oxoglutarate levels, a central carbon-nitrogen balance indicator. In nitrogen-limiting conditions, NtcA triggers genes responsible for nitrogen uptake and assimilation, such as glnA (GS), nirA (NiR), and more. The post-translational regulation is also controlled by the PII protein family (for example, GlnB) by sensing the intracellular level of energy and nitrogen and altering the enzyme function accordingly.

Epigenetic control, such as histone modification and chromatin remodeling, is also becoming a significant level of gene regulation in higher plants, influencing the accessibility of promoters of nitrogen assimilation genes to transcriptional machinery.

In addition, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been reported to target mRNAs of nitrogen-related enzymes, providing an additional mechanism of fine-tuned regulation. For instance, rice miR444 controls MADS-box transcription factors that are part of nitrogen response pathways.

Together, genetic control of nitrogen assimilation enzymes comprises a sophisticated web of transcription regulators, signal transduction circuits, feedback inhibition loops, and environmental signals that maintain nitrogen metabolism finely tuned to internal physiological conditions and external nutrient supply.

Environmental factors affecting assimilation

Plant and microbial nitrogen assimilation is an extremely sensitive process, with a wide range of environmental parameters. Such extrinsic factors could stimulate or hinder nitrogen uptake as well as incorporation into organic forms such as amino acids. Factors affecting assimilation are-

Soil nitrogen availability– The most important is soil nitrogen availability in the forms of nitrate (NO₃⁻) and ammonium (NH₄⁺). The quantity and type of nitrogen in the soil govern which uptake and assimilation processes are initiated. The assimilation of nitrate, for example, is more energy demanding than ammonium assimilation, and the plant’s preference can change with availability, pH, and root zone conditions.

Soil pH- It is also a significant factor. Acidic soil conditions increase concentrations of ammonium through lower nitrification rates, whereas higher pH conditions facilitate nitrate stability. Very low or very high pH levels will, however, interfere with the functioning of enzymes, roots, and microbial processes, all of which are essential for the effective assimilation of nitrogen.

Light– Intensity of light and photoperiod are important determinants of the expression of genes related to nitrogen assimilation, especially those for nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase, which are light-induced. These enzymes utilize NADH and ferredoxin as electron donors, which are generated during photosynthesis. Hence, assimilation efficiency is intimately connected with photosynthetic activity and carbon metabolism.

Temperature– Temperature influences enzyme kinetics and membrane transport mechanisms. Temperate temperatures tend to favor effective nitrogen assimilation, whereas severe cold and heat may inhibit enzyme function (e.g., nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase), decrease root uptake, and modify hormonal signaling pathways such as nitrogen sensing.

Water– Availability of water is also an essential factor. Dry conditions decrease the rate of transpiration and thus cause lower transport of nitrate to the roots and decreased root activity. Conversely, anaerobic conditions in waterlogged soils support denitrification and loss of available nitrogen as gaseous species (e.g., N₂ or N₂O) and lower the assimilable pool of nitrogen.

Oxygen supply– Oxygen supply, particularly in waterlogged or poorly aerated soils, may restrict the aerobic microbial activities that render nitrogen usable by plants (e.g., nitrification) and may impede root respiration, which in turn affects nitrogen assimilation.

Salinity– Salinity and heavy metal pollution in soil can impair the function of the roots, the uptake of nutrients, and activities of enzymes, to decrease the plant’s capacity for nitrogen assimilation. For instance, salinity can trigger ionic imbalances and oxidative stress, which can inactivate important enzymes such as glutamate synthase (GOGAT) and glutamine synthetase (GS).

Major differences between nitrogen assimilation and nitrogen fixation

Nitrogen assimilation and nitrogen fixation are two separate but related processes in the nitrogen cycle.

Nitrogen assimilation is the process of transforming inorganic forms of nitrogen like nitrate (NO₃⁻) or ammonium (NH₄⁺) into organic molecules like amino acids and nucleotides in plants, algae, and most microorganisms. This reaction is mainly catalyzed by enzymes like nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, GS, and GOGAT and involves moderate energy investments in the form of ATP and reducing factors.

Nitrogen fixation, on the other hand, is the biological reduction of atmospheric nitrogen gas (N₂) to ammonium by a group of specialized microorganisms called diazotrophs, comprising species like Rhizobium, Azotobacter, and some cyanobacteria. Nitrogenase, an oxygen-sensitive enzyme, catalyzes nitrogen fixation and requires a large energy investment of approximately 16 ATP molecules for each N₂ molecule reduced.

Nitrogen assimilation enables organisms to utilize existing nitrogen from soil or the environment, whereas nitrogen fixation adds new bioavailable nitrogen to ecosystems, mainly in nitrogen-poor soils. Both functions sustain the nitrogen cycle in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

Augmentation of Crop Nitrogen-Use Efficiency via Assimilation Pathways

Enhancing nitrogen-use efficiency (NUE) in crops is a vital objective in recent agriculture, especially because of the economic and environmental expenses related to nitrogen fertilizers. NUE is the plant’s capability to uptake, assimilate, and mobilize nitrogen for development and growth. Augmenting NUE via advanced pathways of nitrogen assimilation presents a sustainable means to enhance crop yield without increasing nitrogen losses and pollution.

Nitrogen assimilation is the process of transforming inorganic nitrogen compounds—mainly nitrate (NO₃⁻) and ammonium (NH₄⁺) into organic compounds such as amino acids, nucleotides, and chlorophyll. Increasing the activity or regulation of major enzymes involved in this process, including nitrate reductase (NR), nitrite reductase (NiR), glutamine synthetase (GS), and glutamate synthase (GOGAT), is one of the major goals for improving NUE. For example, overexpression of GS and GOGAT at the genetic level has been reported to enhance ammonium assimilation and biomass yield in rice and maize under nitrogen-limited conditions.

Optimization of root structure and transport proteins like nitrate transporters (NRTs) and ammonium transporters (AMTs) to enhance nitrogen uptake efficiency is another approach. Increasing the expression or sensitivity of these transport proteins allows crops to take up more nitrogen from the soil, particularly under low-nitrogen conditions.

Molecular breeding and genetic engineering provide the means of introducing genes with high-efficiency nitrogen assimilation from other life forms (e.g., algae or bacteria) or creating plants with altered regulation pathways. Such as, changing transcription factors associated with nitrogen-responsive gene networks has the potential to upregulate genes related to assimilation in stress or low-nutrient conditions, supporting growth at diminished fertilizer input.

Another potential strategy is the alteration of carbon-nitrogen metabolic equilibrium, since nitrogen assimilation is closely coupled with carbon metabolism. Provision of adequate carbon skeletons and reducing power (e.g., NADH, ferredoxin) may assist in sustaining effective functioning of the GS-GOGAT cycle, particularly under stress situations such as drought or high temperature.

In addition, the application of helpful rhizosphere microbes like nitrogen-fixing bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi can indirectly improve assimilation by enhancing the bioavailability of nitrogen and the health of plants. These microbes also induce the expression of plant genes that participate in nitrogen uptake and metabolism.

Techniques to Measure Nitrogen Assimilation Rates

Understanding nitrogen assimilation in plants and microbes requires reliable and accurate measurement techniques.

One of the most accurate techniques is isotopic tracing with nitrogen-15 (¹⁵N), in which labeled nitrate or ammonium is added to organisms, and its incorporation into proteins and amino acids is followed by mass spectrometry. Enzyme activity assays are also commonly employed, enabling scientists to quantify the activity of important enzymes such as nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, GS, and GOGAT in tissue extracts. Gene expression profiling, e.g., quantitative PCR (qPCR) or RNA sequencing, reveals the impact of environmental conditions on the transcription of assimilation genes.

Metabolite profiling, especially the determination of amino acids such as glutamine and glutamate, can be used as an indirect measurement of assimilation efficiency.

The chlorophyll content or SPAD meter readings can also serve as rapid proxies for nitrogen status in plants, but they are not direct measures of assimilation. These varied methods are essential tools in basic research and applied agronomy to refine nitrogen management practices and augment biological insight.

Predominant Nutrient Deficiencies Affecting Assimilation

Nitrogen assimilation is a metabolically expensive process involving a subtle interaction of several nutrients. Among them, the lack of key macro and micronutrients can drastically hinder the uptake and assimilation of nitrogen in plants and microbes.

Sulfur is an essential nutrient since it is needed for the formation of some amino acids, such as cysteine and methionine, which are end products of nitrogen metabolism. A sulfur deficiency restricts protein biosynthesis and interferes with nitrogen assimilation processes. Iron, too, is a key cofactor, particularly for nitrate and nitrite reductase enzymes. The reduction of nitrate to nitrite and then to ammonium becomes less efficient in the absence of sufficient iron.

Molybdenum is a trace element but essential for the effective operation of nitrate reductase; even a minimal deficiency leads to nitrate accumulation and ineffective nitrogen assimilation.

Magnesium, necessary for chlorophyll and the formation of ATP, aids in the energy-requiring processes of nitrogen assimilation and the biosynthesis of amino acids. Phosphorus, too, is critical for energy transfer through ATP, in the absence of which assimilation reactions are impossible.

Deficiency in these nutrients not only restricts the utilization of nitrogen but also causes visible signs such as chlorosis, dwarfing, and decreased yield. Therefore, a well-balanced nutrient composition is necessary to facilitate effective nitrogen assimilation and plant health.

Conclusion

Nitrogen assimilation is a key process in both plant and microbial physiology, as it is the interface between inorganic sources of nitrogen and biologically important organic compounds. It consists of a coordinated series of enzymatic processes, reduction of nitrate and nitrite, incorporation of ammonium through the GS-GOGAT pathway, and occasionally alternative routes such as GDH. The complex process is controlled at a variety of levels: genetically, environmentally, and through nutrient supply. Although nitrogen fixation adds newly reactive nitrogen to ecosystems, assimilation guarantees its incorporation into amino acids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Enrichment of our knowledge about these pathways provides important hints for increasing agricultural productivity, reducing fertilizer reliance, and ensuring ecological sustainability. As a result of progress in biotechnology and molecular biology, regulation of nitrogen assimilation pathways has become a promising way to increase nitrogen-use efficiency and provide global solutions to food security problems.

Nonetheless, this potential is achieved through collaborative action on research, sustainable production, and management of resources in order to have effective and prudent utilization of nitrogen in the environment.

References

- Admin. (2023, July 28). Nitrogen assimilation. BYJUS. https://byjus.com/neet/nitrogen-assimilation/

- Masclaux-Daubresse, C., Daniel-Vedele, F., Dechorgnat, J., Chardon, F., Gaufichon, L., & Suzuki, A. (2010). Nitrogen uptake, assimilation, and remobilization in plants: challenges for sustainable and productive agriculture. Annals of Botany, 105(7), 1141–1157. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcq028

- Strock, J. (2008). Ammonification. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 162–165). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008045405-4.00256-1

- Kojima, S., Konishi, N., Beier, M. P., Ishiyama, K., Maru, I., Hayakawa, T., & Yamaya, T. (2014). NADH-dependent glutamate synthase participated in ammonium assimilation inArabidopsisroot. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 9(8), e29402. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.29402

- Balotf, S., Kavoosi, G., & Kholdebarin, B. (2015). Nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, glutamine synthetase, and glutamate synthase expression and activity in response to different nitrogen sources in nitrogen‐starved wheat seedlings. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry, 63(2), 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/bab.1362

- Muro-Pastor, M., & Florencio, F. J. (2003). Regulation of ammonium assimilation in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 41(6–7), 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0981-9428(03)00066-4

- Xu, P., & Wang, E. (2023). Diversity and regulation of symbiotic nitrogen fixation in plants. Current Biology, 33(11), R543–R559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.04.053

- Ullah, S., & Ali, I. (2025). Understanding the Molecular Mechanisms of Nitrogen Assimilation in C3 Plants under Abiotic Stress: A Mini Review. Phyton, 0(0), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064608

- Mokhele, B., Zhan, X., Yang, G., & Zhang, X. (2012). Review: Nitrogen assimilation in crop plants and its affecting factors. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 92(3), 399–405. https://doi.org/10.4141/cjps2011-135

- Ali, A., Jabeen, N., Farruhbek, R., Chachar, Z., Laghari, A. A., Chachar, S., Ahmed, N., Ahmed, S., & Yang, Z. (2025). Enhancing nitrogen use efficiency in agriculture by integrating agronomic practices and genetic advances. Frontiers in Plant Science, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1543714

- Naqvi, T. H., & Abbas, S. (2024). The Essential Plant Nutrients; Their deficiency and toxicity symptoms. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380540052_The_Essential_Plant_Nutrients_Their_deficiency_and_toxicity_symptoms

- Kang, Y., Kudela, R. M., & Gobler, C. J. (2017). Quantifying nitrogen assimilation rates of individual phytoplankton species and plankton groups during harmful algal blooms via sorting flow cytometry. Limnology and Oceanography Methods, 15(8), 706–721. https://doi.org/10.1002/lom3.10193

Ich denke das ist die beste Zusammenfassung über die Aufnahme und Assimilation von Nitrat und Ammonium in Pflanzen, die ich je gelesen habe. Interessant wäre auch, wenn die Autorin in ihren Aufsatz auch Flechten einbeziehen würde. Flechten nehmen durch die Symbiose von Alge und Pilz eine besondere Stelle bei der N-Assimilation ein. Darüber ist noch zu wenig bekannt, z. B. über die N-Assimilation in oligotrophen und nitrophilen Flechten. Assimilieren nitrohile Flechten N auch über Carbamylphospat zu Arginin und wird Arginin wieder zu CO2 und Ammoniak abgebaut womit wieder Glutamat synthetisiert wird(Harnstoff-Zyklus).