Water Potential (Ψ) deals with how the potential energy of a plant is measured. Relative movement of water and two systems, water potential and its movement, water is calculated using a specific factor, Megapascals (MPa). The two major factors that affect water potential include solute potential (Ψs) and pressure potential (Ψp).

Solute potential– Also called osmotic potential, solute potential is one of the measures of free energy and is always negative due to the presence of solutes.

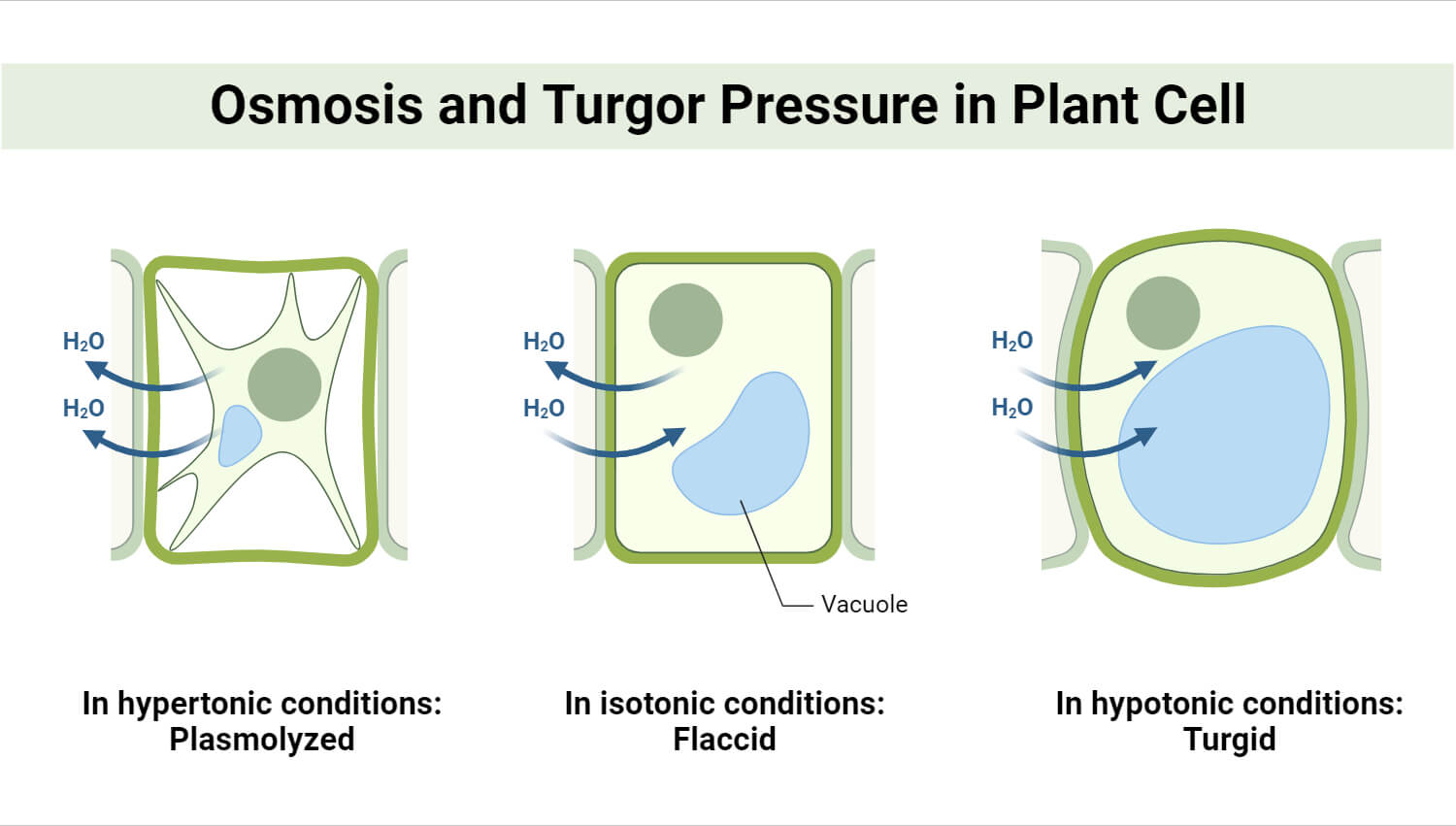

Pressure potential– The turgid/tensile condition of a cell defines the positive or negative degree of pressure potential. In most situations, pressure potential is positive in a cell that is healthy and turgid. This is a result of water being osmotically drawn into the vacuole of the cell, which causes the membrane to be forced against the cell wall.

In a plant cell, the total water potential is given by Ψ = Ψs + Ψp. Water moves from a less negative water potential to a more negative water potential. This gradient is responsible for the uptake of water from the soil, its movement within the plant vascular system, and its final loss through transpiration. Water potential is the key for understanding how plants are hydrated, turgor pressure is developed, and nutrients are transported in varying environmental conditions.

Absorption of Water by Roots

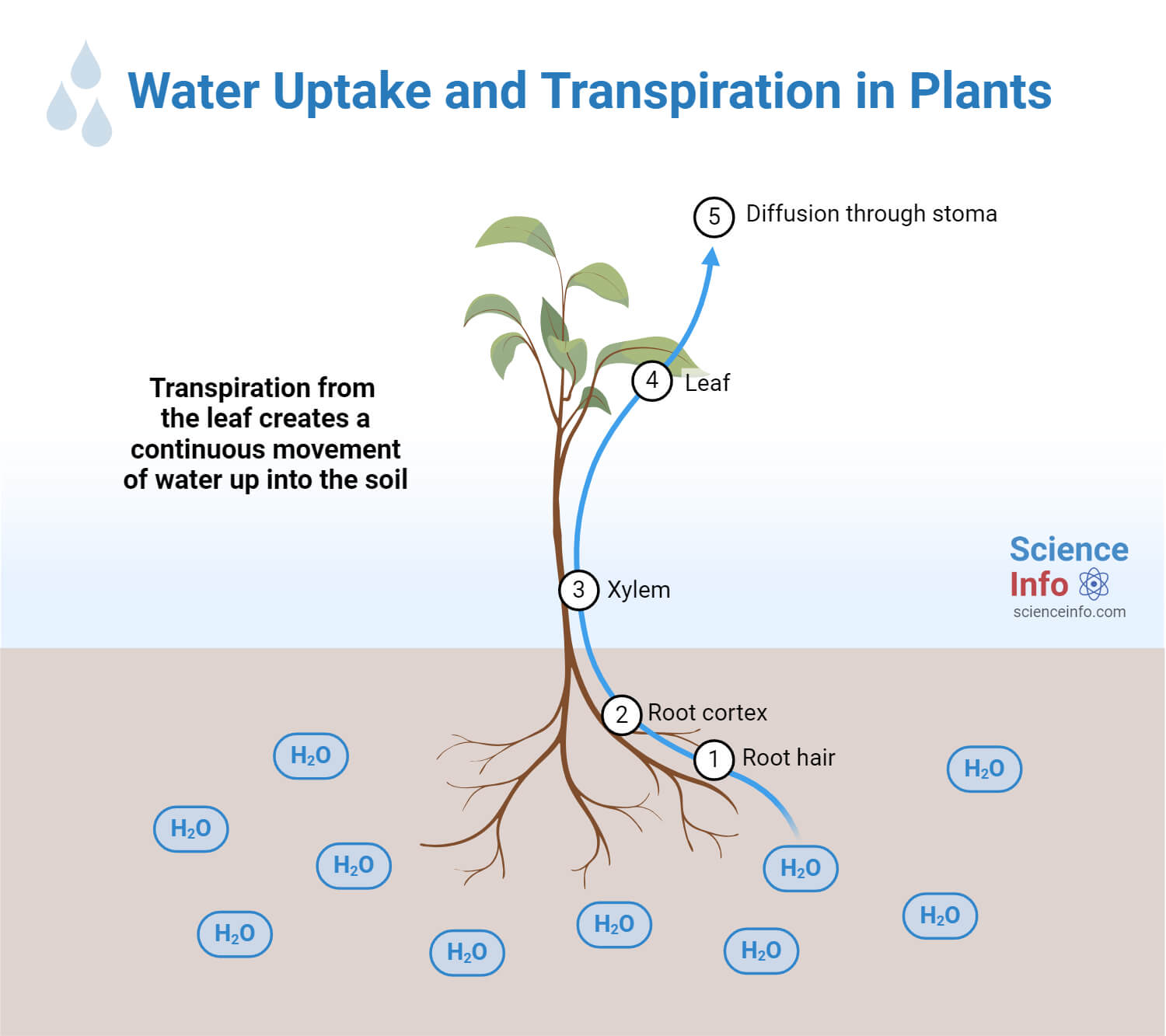

The primary site of water absorption from the soil is the root region in plants, which possesses a root hair. These are the elongated epidermal cells and are the most active region of water absorption. A root hair cell has an outer cell wall, which is made with pectin, with an inner layer comprising cellulose. The cell wall encloses a selectively permeable cytoplasm membrane region constricting passage to the cell or cytoplasmic membrane, thus maintaining homeostasis.

The process involved in the drawing of water into the root occurs mainly through osmosis. The soil region has a higher water potential level compared to the root cells region.

Absorption of water by most plants occurs in one of two ways:

Active water absorption– In active absorption of water, metabolic energy is spent by the cells of roots to carry out metabolic activities, for example, respiration. Plants take up water in two main types: osmotic water absorption and non-osmotic water absorption.

Water absorption by osmosis– This is a type of water absorption where water is taken in through osmosis. The process of active osmosis occurs when water is taken into the xylem of the root through the concentration gradient of the root cell. Because of a high concentration of solutes in the cell sap and a low concentration of the soil surrounding it, osmotic movement occurs.

Nonosmotic water absorption– The process of water absorption in this case occurs when water migrates into the cell from the soil in opposition to the concentration gradient of the cell. Metabolic energy must be expended in the form of respiration to achieve this. So the higher the rate of respiration, the higher the rate of water absorption. Auxins are used for stimulating growth, and they increase the respiring processes in the plants, therefore increasing the amount of water absorbed.

Passive Absorption of Water – In this form of water absorption, there is no expenditure of metabolic energy. Water absorption occurs due to metabolic activities. Passive absorption is the type of water absorption that occurs as a result of the transpiration pull. It creates tension or a force that aids in the elevation of the xylem sap and water column. Water absorption and loss through transpiration are directly related.

Water Movement Pathways: Apoplast and Symplast

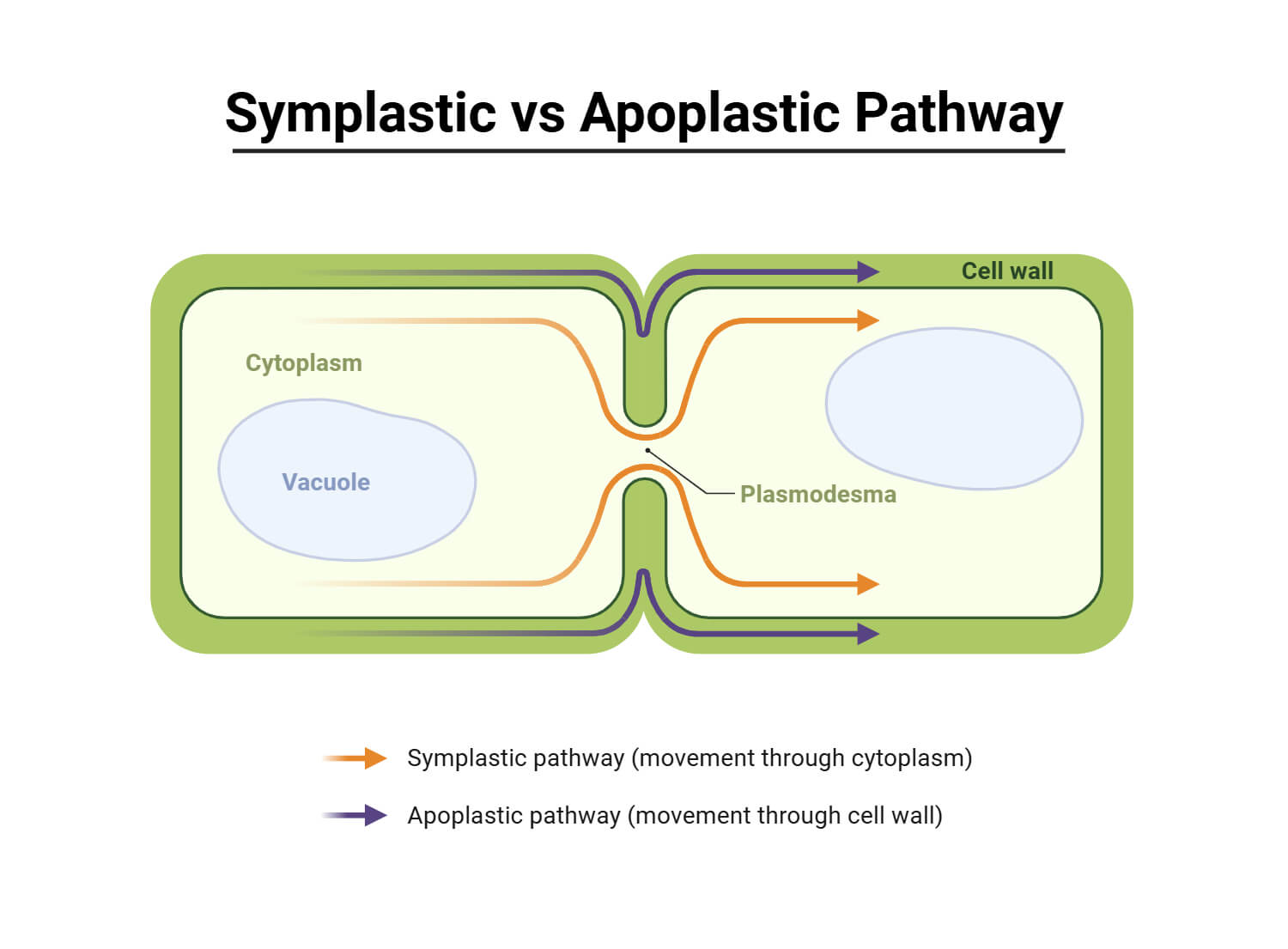

Once the water reaches the root from the epidermal cells and root hairs, it has to go through the cortex so as to reach the vascular tissue or the xylem. While doing so, water can take three interrelated ways: the apoplast, symplast, and transmembrane pathways.

However, equally important in determining the effectiveness and controlling the transport of water in the plant are the apoplast and symplast pathways.

Apoplast – Passive movement of water in water through the walls of cells and in the spaces between the cells without entering the cell’s cytoplasm is termed the apoplast pathway of transport. The route met with less resistance and thus made a quicker transport more likely, especially in the tissues where the continuity of the cell wall is unbroken.

Symplast– The symplast pathway involves water movement between cells via cytoplasm, which is linked by plasmodesmata, fine channels connecting bordering cells. With this path, water penetrates the cell through the plasma membrane and proceeds through the symplastic continuum. This path offers selective permeability so that the plant can filter and control ions as well as solute movement more selectively.

Both these pathways usually function together. Water might flow through the apoplast in the cortex initially, but is compelled to switch into the symplast at the endodermis because of the Casparian strip. The mixed model of water flow through this enables a balance between speed and selectivity, an essential characteristic in supporting homeostasis and optimizing resource allocation within the plant body.

What is Transpiration?

Transpiration is the physiological process by which water is lost by plants in the form of vapour to the outside air, mainly through their leaves. Most of this loss takes place through stomata, though lesser pathways are the cuticle and lenticels. Transpiration starts at the mesophyll cells, where water evaporates from the wet cell walls into the intercellular air spaces. This vapor also diffuses from the stomatal pore to the external environment, propelled by a pressure gradient in the vapor.

Although it may seem paradoxical for plants to lose water, transpiration plays several critical physiological roles. Most prominently, it is a primary force behind the transpirational pull, a negative pressure that aids in the transport of water and soluble minerals upward from the roots to the aerial surfaces of the plant. This one-way transport, often referred to as the transpiration stream, is essential for nutrient delivery, turgor pressure, and hydration of cells.

Transpiration also plays a role in the plant’s thermoregulatory system. As water is evaporating off the leaf surface, it takes latent heat with it and cools the plant, an especially vital function in high-radiation or desert environments. In addition, it causes an ongoing stream of water to circulate through the plant, facilitating the supply of nutrients to the developing tissue and the upkeep of the biochemical equilibrium.

But overwater loss can cause physiological drought, particularly when high temperatures, low humidity, or high winds prevail. Plants have therefore developed an array of regulation mechanisms, stomatal closure, leaf adaptations, and alterations in cuticular characteristics to maximize transpiration about environmental factors.

Cohesion-Tension Theory of Water Transport

The cohesion-tension theory, first articulated by Dixon and Joly in the late 19th century, remains the most widely accepted explanation for the ascent of sap in vascular plants. It posits that water is pulled upward through the xylem due to the cohesive forces between water molecules and the tension created by transpiration at the leaf surface.

This concept is supported by three mutually dependent physical principles: cohesion, adhesion, and tension caused by transpiration.

Cohesion– Cohesion is the strong hydrogen bond between water molecules that enables them to constitute a continuous column within the tiny lumen of the xylem vessel.

Adhesion– Adhesion is the force of attraction between the water molecules and the hydrophilic walls of xylem vessels that supports the water column against gravity.

As transpiration takes place, water evaporates from the walls of mesophyll cells, reducing their water potential. The tension that builds up is transferred downward by the continuous column of water in the xylem. The negative pressure pulls water from the roots towards the leaves upwards without any expenditure of metabolic energy by the plant.

The model accounts for why tall trees are able to transport water to heights of over 100 meters. Yet, it is not without weaknesses. The water column may rupture under high tension, causing cavitation or embolism, the formation of air bubbles within the xylem vessels. Plants counter these hazards through duplicate vessel systems, bordered pits, and refilling mechanisms of xylem elements. Although simple, the cohesion-tension theory beautifully unites the physical properties of water with plant physiology to describe long-distance water transport.

Role of Xylem and Phloem in Water Transport

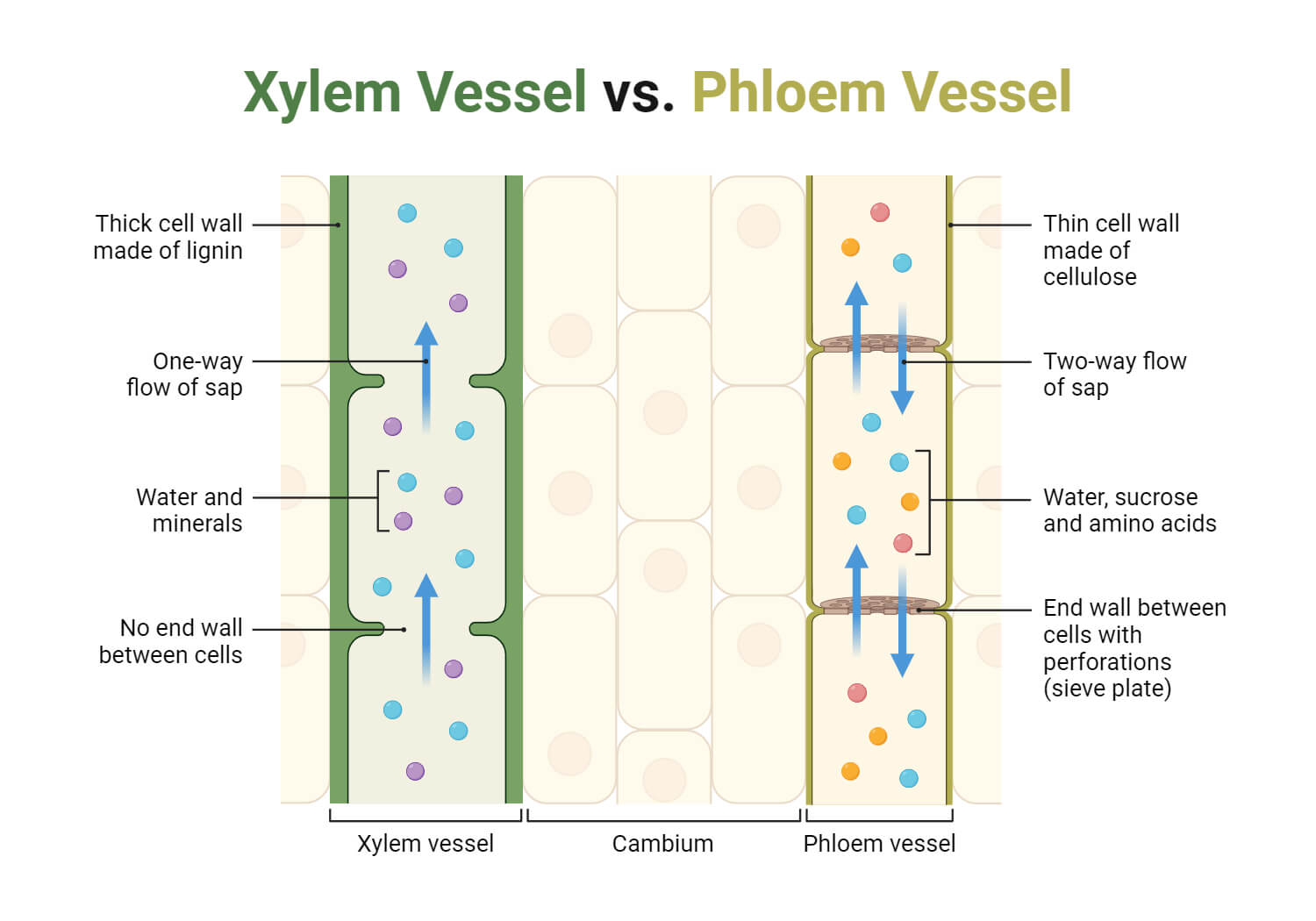

Vascular plants have two specialized tissues for internal transport, namely xylem and phloem, with different roles for water and solute distribution. Whereas the major role for upward water and dissolved minerals transport from roots to shoots lies with the xylem, phloem is involved in the bidirectional movement of organic nutrients, primarily sugars produced during photosynthesis.

The xylem is composed of lignified, dead, hollow tracheary elements that include vessel elements and tracheids. These are arranged in a continuous pipeline from leaf to leaf, the root, and present very little resistance to the flow of water. Movement in the xylem is established by the transpiration pull, is regulated by water potential differences, and does not involve any metabolic energy. In addition to transport, xylem also gives structural support owing to the thick, lignified walls of its vessels.

In comparison, the phloem contains living sieve tube elements, companion cells, phloem fibers, and parenchyma. Phloem transport, or translocation, is an energy-requiring process that encompasses the transport of photo assimilates from the source (usually mature leaves) to the sink (roots, fruits, or developing tissues). Water helps in this process by creating a hydrostatic pressure gradient across the source and sink areas, often coupled with xylem to ensure osmotic equilibrium.

Xylem and phloem work together to regulate the transport of water, nutrients, and signaling substances, thereby ensuring the integrated behavior of the plant. The complementarity of their roles is a paradigm of the complexity of vascular transport systems developed in plants on land to counteract the constraints of size, height, and environmental heterogeneity.

Stomatal Regulation and Water Loss Control

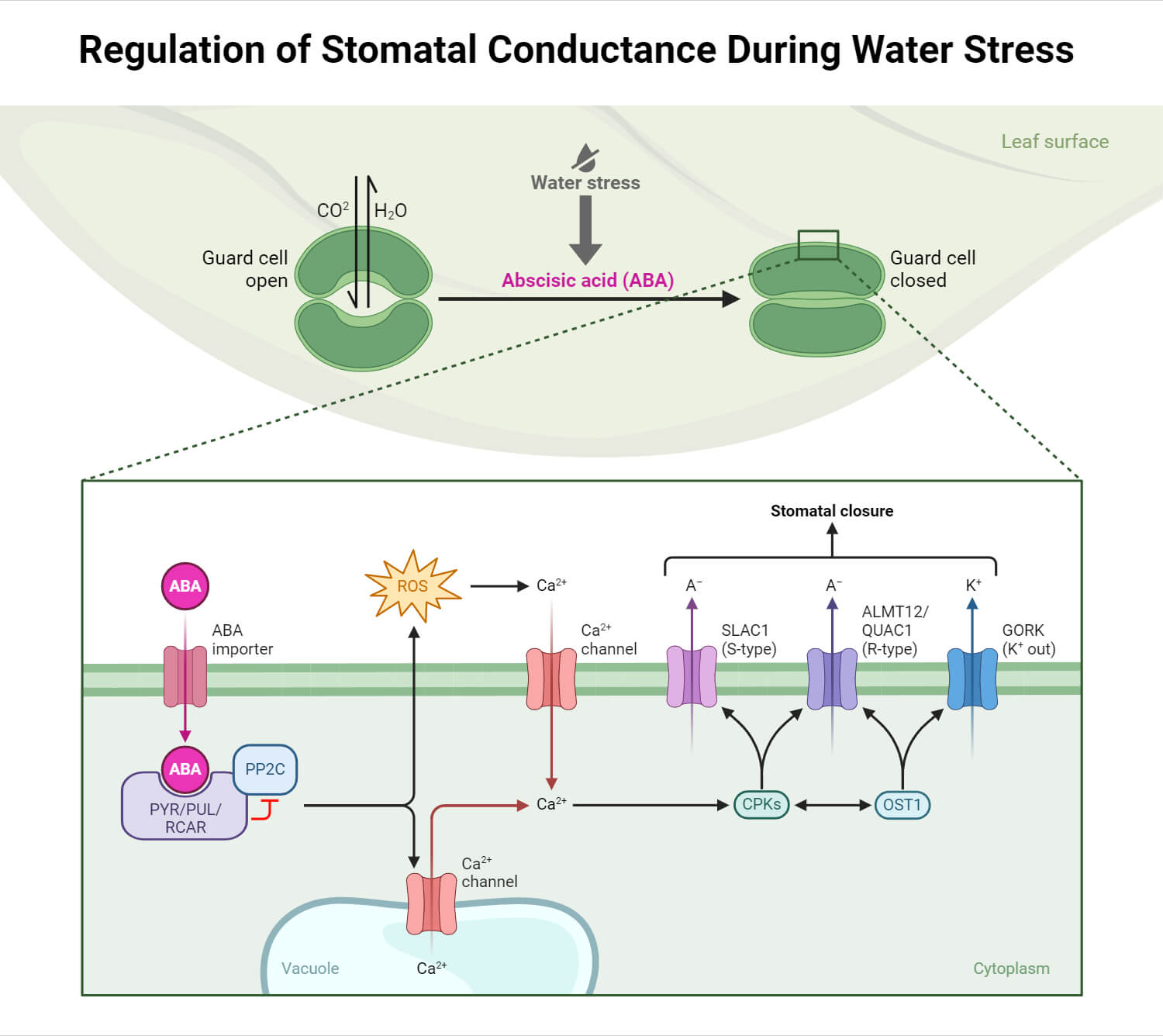

Stomata are minute pores found on leaves and stems’ epidermis, encircled by specialized guard cells that control their opening and closure. The structures play a critical role in ensuring water balance and maximizing gas exchange in plants. Stomatal behavior is influenced by a combination of internal signals such as turgor pressure, hormonal cues (e.g., abscisic acid), and circadian rhythms, and external environmental factors including light intensity, humidity, carbon dioxide concentration, and soil moisture availability.

In well-hydrated conditions, guard cells become turgid due to osmotic influx of water following active accumulation of potassium ions. This turgidity causes the guard cells to bow outward, opening the stomatal pore. Conversely, during water stress or in response to ABA signaling, ion efflux leads to loss of turgor, causing the stomata to close and minimizing water loss. This dynamic regulation allows the plant to balance the competing demands of carbon dioxide uptake for photosynthesis and minimization of water loss via transpiration.

Plants have also developed morphological and anatomical features to improve stomatal control. For example, sunken stomata, stomatal crypts, and thick cuticles are typical of xerophytes, minimizing transpiration by establishing localized microenvironments with increased humidity. In CAM (Crassulacean Acid Metabolism) plants, stomata are open at night to restrict water loss during the day, a metabolic adaptation to arid habitats.

Stomatal control is therefore a highly adjusted physiological mechanism that underlies water-use efficiency, stress resistance, and production, particularly under the continually fluctuating conditions induced by climatic change. The intricacy of this process highlights the advanced feedback system utilized by plants to survive in various environments.

Soil-Plant-Atmosphere Continuum (SPAC)

The Soil-Plant-Atmosphere Continuum (SPAC) is the dynamic, integrated sequence along which water travels from the soil to plant roots, up through the xylem, and finally lost to the atmosphere through transpiration. The continuum follows water potential gradients, from higher in the soil to increasingly lower potentials within the plant and atmosphere.

Water absorption starts in the rhizosphere, where it enters into epidermal cells of roots and moves through the apoplastic and symplastic pathways until it reaches the xylem. The properties of cohesion and adhesion in water enable it to move up under tension through vessels in the xylem, a function explained by the cohesion-tension theory. Finally, water departs via stomata due to the vapor pressure deficit between the leaf interior and the exterior air.

SPAC is critical to consider in plant-water relationships since it combines soil moisture availability, the physiological response of the plant, and atmospheric demand. Interruption of any segment of the continuum because of drought, root injury, or excessive evaporative demand will considerably affect water transport and plant function.

Effect of Environmental Factors

Environmental factors, including light intensity, temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and soil conditions, affect plant water relations considerably. All these factors regulate transpiration rates and, by extension, water uptake and movement within plants.

Light– Increase in light leads to the opening of stomata, which enhances transpiration. At high light, guard cells are triggered to swell, causing stomatal pores to open for gaseous exchange and water loss.

Temperature- Temperature influences the vapor pressure deficit. High temperatures enhance the driving force for transpiration but can also cause wilting due to excessive water loss over water uptake.

Humidity– Humidity has an inverse relationship with rates of transpiration. Low humidity enhances the gradient for water vapor flow from leaf to air, leading to accelerated water loss.

Wind– Wind removes the humid air boundary layer from leaves, increasing transpiration. Long-term exposure to wind might require physiological adaptations like small leaves or thick cuticles.

Soil- Soil conditions, especially water content and salinity, have a direct effect on water potential at the soil-root interface. Saline or dry soils reduce water potential, making it more difficult for roots to take up water.

It is necessary to know these environmental factors because they influence irrigation requirements and the choice of plant varieties optimally adapted to particular climates.

Plant adaptations to Water Stress

Plants growing in arid or drought-prone conditions display a variety of structural, physiological, and biochemical adaptations to conserve water and make the most efficient use of it.

Morphological adjustments are in the form of lowered leaf surface area (as with needle-shaped leaves), cuticle thickening, stomatal depression, and hairiness of leaves, all of which reduce transpiration.

Physiological processes like closure of stomata, osmotic adjustment (solute accumulation, such as proline), and lowered growth of the shoot enable cellular turgor and metabolic activity under water-deficient conditions.

Alterations in the root system, such as deeper or longer lateral roots, increase water uptake from lower soil horizons.

CAM and C4 photosynthesis mechanisms enable some plants to conserve water by separating temporally carbon fixation from the Calvin cycle, lowering the demand for open stomata during the day.

These strategies not only enable survival in water-limited environments but also provide important attributes for crop improvement under climate change.

Measuring Plant Water Status

Correctly measuring plant water status is important for research and agricultural management. Various direct and indirect techniques are used:

Pressure chamber (Scholander bomb): This method scales leaf water potential by measuring the pressure needed to push water from a cut petiole.

Psychrometry: It measures the relative humidity of air in equilibrium with plant tissue, returning values for water potential.

Chlorophyll fluorescence: This is an indirect method, but changes can reflect dehydration stress, affecting the efficiency of photosystem II.

Infrared thermography: This method measures changes in leaf temperature as an indirect sign of transpiration and stomatal conductance.

Soil moisture sensors: It is not a direct measurement of the plant, but they give background information regarding plant water status and possible stress.

These methods differ in accuracy, expense, and simplicity, but, as a group, allow researchers and farmers to observe and control water stress efficiently.

Importance of Plant Water Relations in Agriculture

Water is a basic force that triggers all the physiological and metabolic processes in plants. In agriculture, plant-water relation takes a central position, determining not just the growth and development of crops but also the efficiency of resource utilization and the productivity of agricultural systems. Knowledge of plant water relations enables farmers, agronomists, and scientists to make intelligent choices about irrigation, crop choice, and soil management, which maximizes yield and encourages sustainable agriculture.

Maximizing water use efficiency– As the increasing scarcity of water resources caused by climate change and over-extraction becomes a common issue, effective use of water in agriculture becomes an imperative. Understanding plant water relations aids in the detection of crop growth stages most vulnerable to water stress and scheduling of irrigation in response. The ideas of transpiration efficiency and stomatal conductance allow agronomists to choose crop genotypes and adopt strategies that achieve maximum biomass production per unit of water consumed.

Enhanced irrigation management– Scientific knowledge of plant water potential, soil moisture supply, and evapotranspiration allows for the development of accurate irrigation systems, including drip and sprinkler irrigation. The latter lowers water loss and maintains optimal soil water content. Irrigation scheduling based on plant water status measured with pressure chambers or soil moisture sensors provides timely delivery of water to avoid drought stress and waterlogging.

Crop yield and quality improvement– Plant water status has a direct effect on cellular growth, nutrient acquisition, and photosynthesis. Inadequate water supply can result in limited plant growth, decreased leaf area, accelerated senescence, and eventually reduced yields. On the other hand, excessive water may bring about root anoxia and nutrient loss. Having the right water balance guarantees healthy crop growth, flowering, fruiting, and enhanced product quality, critical for both food crops and high-value horticultural crops.

Selection and Breeding of Stress-Resilient Varieties- Knowledge of water relations directs plant breeders to choose and develop crop varieties that are more suitable for water-limited conditions. Characteristics of deeper roots, osmotic adjustment ability, and good stomatal control are now the focus of breeding programs. Through increased drought tolerance and improved water use efficiency, these varieties help to stabilize yield in fluctuating climatic situations.

Sustainable Soil and Nutrient Management– Water is essential in the dissolution, transport, and uptake of nutrients. Lack of water restricts root activity and nutrient uptake, while excess water can lead to nutrient loss via leaching. Knowledge of the interaction between water and nutrient dynamics is important in coordinating fertilizer application with irrigation to enhance sustainable soil fertility management and minimize environmental pollution.

Climate Change Adaptation– With rising climate variability, knowledge on plant water relations becomes crucial in building resilience in agricultural systems. Droughts, unpredictable rainfall, and high evapotranspiration stress crops, especially in semi-arid and rain-fed areas. Water relation research helps develop adaptive strategies, such as effective water harvesting, choice of appropriate crops, and cultural practice timing.

Conclusion

Plant water relations comprise a multifaceted interaction between the environment, plant physiology, and soil. Water movement within the soil-plant-atmosphere continuum is essential to maintain metabolic functions, facilitate growth, and guarantee crop productivity. Comprehension of the processes of water uptake, transport, and loss and of how plants respond to fluctuating conditions allows scientists and farmers to advance water-use effectiveness and drought resilience. As the growing problem of water shortage faces humanity globally, command of plant water relations is not just a scientific imperative but the pillar of sustainable agriculture and food security.

References

- Knipfer, T., & Cuneo, I. F. (2022). Editorial: Plant-water relations for sustainable agriculture. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.979804

- Admin. (2021, November 18). Apoplast and Symplast. BYJUS. https://byjus.com/biology/apoplast/

- Libretexts. (2022, May 4). 4.5.1.4: Water absorption. Biology LibreTexts. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Botany/Botany_(Ha_Morrow_and_Algiers)/04%3A_Plant_Physiology_and_Regulation/4.05%3A_Transport/4.5.01%3A_Water_Transport/4.5.1.04%3A_Water_Absorption

- Water transport in plants: Xylem | Organismal Biology. (n.d.). https://organismalbio.biosci.gatech.edu/nutrition-transport-and-homeostasis/plant-transport-processes-i/

- Trimble, S. (2022, March 16). Transpiration in Plants: Its importance and applications. CID Bio-Science. https://cid-inc.com/blog/transpiration-in-plants-its-importance-and-applications/

- Rekwar, R. K., Patra, A., Jatav, H. S., Singh, S. K., Mohapatra, K. K., Kundu, A., Dutta, A., Trivedi, A., Sharma, L. D., Anjum, M., Anil, A. S., & Sahoo, S. K. (2021). Ecological aspects of the soil-water-plant-atmosphere system. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 279–302). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-85665-2.00009-1.

- Soil Plant Atmosphere Continuum (SPAC). (2019, February 25). [Slide show]. SlideShare. https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/soil-plant-atmosphere-continuum-spac/133215750.

- Basu, S., Ramegowda, V., Kumar, A., & Pereira, A. (2016). Plant adaptation to drought stress. F1000Research, 5, 1554. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7678.1.

- Asmare, M. T. (2022). Review of plant water status measurement techniques. East African Journal of Forestry and Agroforestry, 5(1), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.37284/eajfa.5.1.850.

- Vedantu, & Vedantu. (2025, May 19). Plant water relations. VEDANTU. https://www.vedantu.com/biology/plant-water-relations.

- Giménez, C., Gallardo, M., & Thompson, R. (2013). Plant–Water relations. In Elsevier eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-409548-9.05257-x.

Good morning, Nirmita ma’am

One correction. In Passive Absorption part, you have mentioned Active absorption instead of Passive absorption.

Dear Ashwit,

Thank you for the correction. We have updated the page.