Plant growth and development depend upon mineral nutrition as a basic necessity. Mineral nutrients are taken up from the soil in their ionic form and serve distinctive biochemical and physiological functions. Out of 17 known essential elements, a few are needed in greater amounts and are referred to as macronutrients, whereas others are required in trace amounts and are referred to as micronutrients.

Every single one, irrespective of amount, is essential and cannot be replaced. Even a single nutritional deficiency can strongly inhibit plant metabolism, structural organization, or reproductive function. These mineral nutrients contribute to important functions such as photosynthesis, activation of enzymes, protein synthesis, and energy transfer.

Hence, it is important to know the nature, role, and absorption of these nutrients to encourage sustainable agriculture and enhance crop yields.

Macronutrients and Micronutrients: Functions and Roles

Both macronutrients and micronutrients are essential for plants, differing in the quantity required but not in importance. Macronutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur are required in relatively large quantities. Nitrogen is essential for amino acid and protein formation, phosphorus for energy metabolism and genetic material, and potassium for enzyme activation and osmotic adjustment. Calcium provides cell wall structural strength, magnesium is important for chlorophyll development, and sulfur assists with some amino acids and vitamins.

On the other hand, micronutrients such as iron, manganese, boron, zinc, copper, molybdenum, and chlorine are required in small quantities but are also crucial. Iron is crucial for the synthesis of chlorophyll and electron transfer, manganese helps in photosynthesis, and boron maintains cell wall rigidity and pollen tube elongation. Zinc is involved in hormone regulation, copper is a constituent of several oxidase enzymes, molybdenum facilitates nitrogen assimilation, and chlorine controls stomatal function. Appropriately balanced availability of both types of nutrients is necessary to provide for maximum plant metabolism, resistance to disease, and reproductive processes.

Mechanism of Mineral Uptake in Plants

Mineral nutrient uptake from the soil is a carefully regulated and energy-requiring activity in plants. Nutrients may pass into root cells through two major methods- passive transport and active transport.

Passive transport– Passive transport is a non-energy-requiring method and takes place along the concentration gradient. During this process, ions permeate the cell membrane or use protein channels without the use of ATP. It is comparatively slower and is accountable for the primary movement of ions from the soil solution into the outer root cells.

Active transport– By contrast, active transport needs to expend energy in the form of ATP to transport ions against their concentration gradient. This process utilizes specialized transporter proteins in the plasma membrane for the selective uptake of nutrients, particularly when their extracellular concentrations are low. ATP-powered pumps like H-ATPase establish electrochemical gradients that help in the uptake of charged ions. The combination of the passive and active mechanisms ensures that plants gain a wide variety of nutrients effectively, even in poor soils.

After nutrients enter the root, they have to pass through internal tissues to access the xylem. The movement occurs through two primary pathways- the apoplastic and symplastic pathways.

Apoplast– The apoplastic pathway is the movement of water and dissolved minerals through intercellular spaces and cell walls without passing through the cell membrane. It permits comparatively quicker transport but is disrupted at the endodermis because of the existence of the Casparian strip- a suberized layer causing substances to have to enter the symplast for selective uptake.

Symplast– Symplastic pathway, on the other hand, is the diffusion of substances via the cytoplasm of root cells, which are linked by plasmodesmata. In this pathway, minerals have to penetrate across the plasma membrane first, but after that, they can travel cell to cell via cytoplasmic linkages. The symplastic pathway provides more control over what enters the vascular system. All these pathways, together, provide efficient transport as well as selective uptake of nutrients before minerals are loaded into the xylem for long-distance transport.

Function of Root Hairs in Absorbing Nutrients

Root hairs are elongated, tubular outgrowths of the root epidermal cells and are the major site for the uptake of water and mineral ions. Root hairs enormously expand the surface area of the root system so that the plant can access more volume of soil and obtain nutrients with greater efficiency. Root hairs are found at proximity to the root tips where growth takes place, and they invaginate between soil particles to provide maximum contact with soil water and dissolved ions.

These structures are essential in the early stages of nutrient acquisition through both passive and active transport mechanisms. Due to direct contact with the soil solution, root hairs take up vital ions such as nitrate, phosphate, potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Thin walls and the absence of a cuticle facilitate the free diffusion of minerals. They also tend to interact with helpful soil microbes and mycorrhizal fungi, increasing nutrient accessibility and uptake.

Plant Transport Systems- Xylem and Phloem

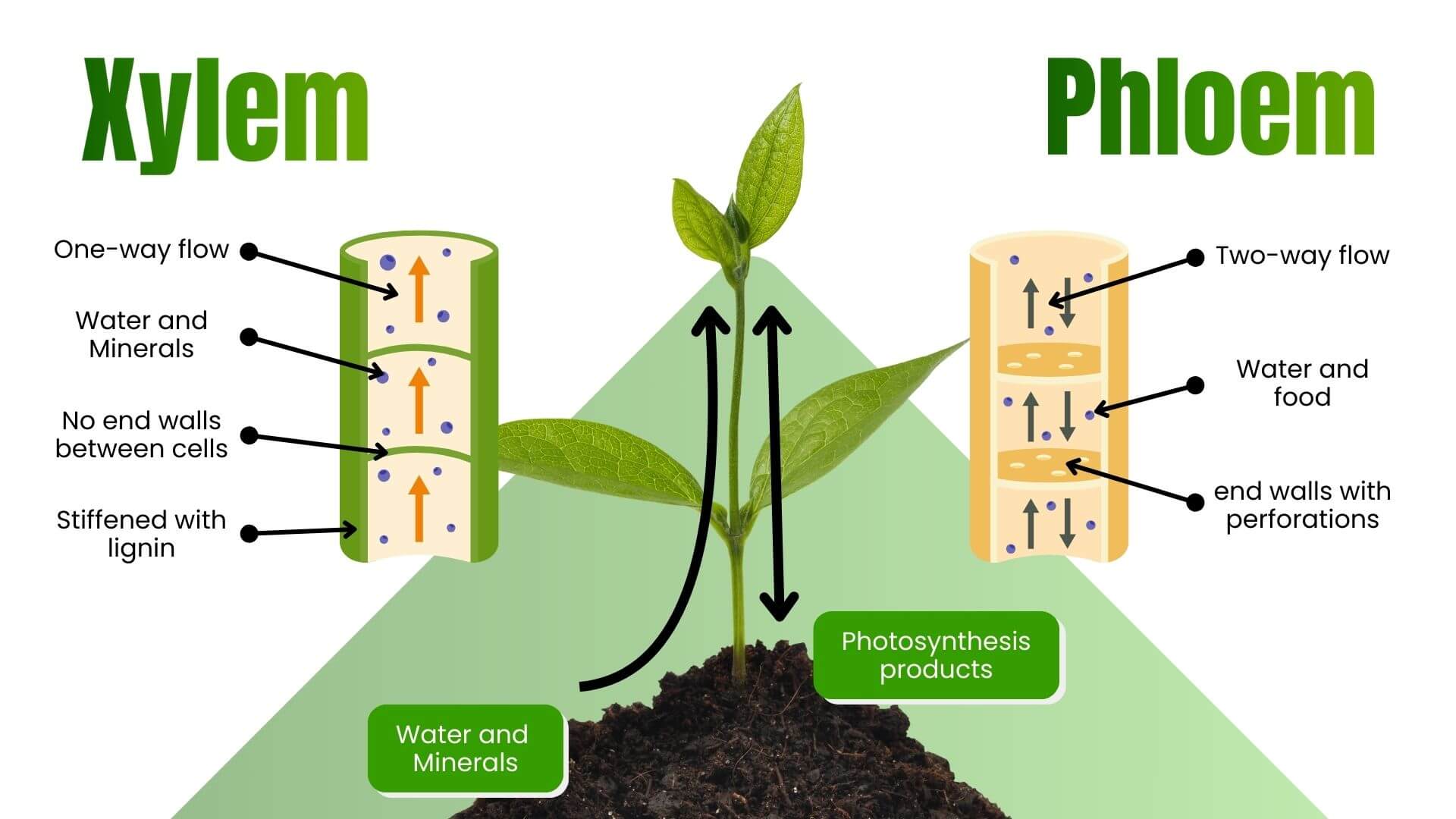

Plants make use of two extremely specialized vascular tissues for internal transport- xylem and phloem. The xylem facilitates the upward movement of water and dissolved minerals from the roots to the shoots. It is primarily made possible by transpiration, a procedure in which water is lost from leaf surfaces, generating a pressure deficit that draws water up the xylem vessels. Xylem is also structurally supportive because of its thick, lignified walls.

The phloem, however, facilitates the bidirectional transport of organic nutrients, particularly sugars such as sucrose, from source tissues (usually leaves) to sink tissues (roots, fruits, and developing parts). Translocation is energy-requiring and happens via living cells like sieve tube elements and companion cells. Proper synchronized function of xylem and phloem provides effective distribution of both water and food in support of all growth, development, and reproduction in plants.

Translocation of Solutes

Translocation is the movement of organic solutes, particularly carbohydrates, within the phloem from the production sites (sources) to utilization or storage sites (sinks). Mature leaves in most plants serve as sources for photosynthesis that result in sugars. These sugars are loaded actively into the phloem and transported under pressure using sieve tubes to sink tissues such as roots, young leaves, flowers, seeds, or storage organs.

The force driving translocation is the pressure-flow hypothesis. Sugars are loaded into phloem at the source and thereby increase osmotic pressure, which pulls in water from the surrounding xylem and results in high turgor pressure. Sugars are unloaded at the sink and decrease osmotic pressure, which allows water to flow back into the xylem. The difference between the turgor pressures forces the sap from the source to sink. The procedure is tightly controlled and crucial to plant energy distribution, reproductive growth, and reaction to the environment.

Factors That Influence Mineral Nutrition and Transport

Plant mineral nutrition and transport efficiency are determined by several internal and external factors. Soil structure, texture, organic matter, and mineral content have a direct impact on the availability of nutrients. Moisture content in the soil determines the solubility and mobility of the ions, while aeration influences root respiration and uptake of nutrients.

Environmental conditions of temperature, light intensity, and humidity also contribute by influencing root metabolism, transpiration, and nutrient transport-related enzyme activities. Internally, plant growth stage, root architecture, membrane transporters, and metabolic requirements control the uptake, transport, and utilization of nutrients. Symbiotic organisms like nitrogen-fixing bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi also influence nutrient dynamics. An awareness of these factors is critical for optimizing fertilization strategies and enhancing crop health.

Deficiency Symptoms of Essential Nutrients

Plants, when deprived of certain essential nutrients, show typical symptoms of deficiency that influence growth, development, and yield. The symptoms depend on the mobility of the nutrient within the plant. For instance, mobile nutrients such as nitrogen (N) and magnesium (Mg) express symptoms in the leaves, starting with the older ones, whereas immobile nutrients such as iron (Fe) and calcium (Ca) impact younger tissues.

- Nitrogen deficiency causes chlorosis (yellowing) of older leaves and dwarfing.

- Phosphorus deficiency causes dark green or purplish coloration, particularly in leaves and stems.

- Potassium deficiency produces yellowing along the margins of leaves and slender stems.

- Calcium deficiency can cause blossom end rot of fruits and root development.

- Iron deficiency manifests as interveinal chlorosis in young leaves.

- Early detection of such symptoms is essential for corrective management using specific fertilization or soil application.

Soil pH and How It Affects Nutrient Availability

Soil pH is the determining factor in the availability of nutrients to plants. The majority of nutrients are available between 6.0 and 7.5, slightly acidic to neutral. Beyond these limits, some nutrients become insoluble or toxic.

In acidic soils (pH low), metals such as aluminum, manganese, and iron can build up to toxic concentrations, whereas phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium become less accessible.

In alkaline soils (high pH), micronutrient availability, such as iron, zinc, copper, and manganese, declines, usually resulting in deficiency.

Soil pH influences the activity of soil microorganisms that cycle nutrients as well. Soil testing regularly and pH modification by adding lime to increase pH or sulfur to decrease pH will improve nutrient availability and plant growth.

Mycorrhizal Associations and Nutrient Uptake

Mycorrhizae are symbiotic relationships between plant roots and specific soil fungi. Fungi infect the surface of roots and push hyphae into the ground, considerably enhancing the surface area for absorption. As a reward for sugars from the plant, mycorrhizal fungi allow the absorption of immobile nutrients such as phosphorus, zinc, and copper.

Two large categories of mycorrhizae exist:

Ectomycorrhizae, sheathing roots, are found in trees.

Arbuscular mycorrhizae (AM), which penetrate root cells and are prevalent in most crop plants.

Mycorrhizal associations improve plant stress tolerance, enhance soil structure, and promote long-term soil fertility. They also reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers, making them valuable tools in sustainable agriculture.

Techniques to Enhance Nutrient Use Efficiency

Improving Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE) is essential for maximizing crop productivity while minimizing environmental impact. Key strategies include:

Balanced Fertilization: Use of nutrients in the right ratio according to soil testing avoids deficiencies and toxicities.

Split Applications: Split application of fertilizer doses minimizes loss through leaching or volatilization.

Slow-Release Fertilizer Use: Formulations that release nutrients steadily over long periods.

Foliar Feeding: Direct application of nutrients to leaves prevents quick deficiencies from being set up to correct.

Soil Amendments: Incorporation of organic matter, biochar, or beneficial microbes enhances nutrient storage and root health.

Precision Agriculture: GPS and sensor technologies enable site-specific nutrient management.

Crop Rotation and Intercropping: These techniques increase soil fertility and decrease nutrient depletion.

Farmers can have better yields with reduced input costs and less environmental degradation by using these methods.

Environmental Stress and How It Affects Nutrient Transport

Plants are frequently exposed to environmental stresses like drought, salinity, temperature, waterlogging, and heavy metal pollution — all of which have a profound impact on nutrient uptake, transport, and use.

Drought stress– It decreases the availability of water in the soil, inhibits the solubility of nutrients, and reduces root growth. As the rate of transpiration decreases, the passive transport of nutrients like nitrogen and calcium is lowered.

Salinity– Salinity stress adds extra sodium and chloride ions, which interfere with potassium, magnesium, and nitrate absorption. Salinity stress can upset ion balance and induce osmotic stress.

Temperature– Excessive or low temperatures change root metabolism and membrane fluidity, and lower active transport processes.

Flooding– Flooding or waterlogging reduces oxygen supply in soil, impacting root respiration and restricting the energy needed for active uptake of nutrients.

Plants can react by adaptive mechanisms like enhanced expression of stress-associated transporters, production of compatible solutes, and symbiosis with stress-tolerant mycorrhizae. The knowledge of such physiological responses is essential to crop breeding and management for tolerance to climate change.

New Advances in Fertilizer Application for Improved Nutrition

Several new methods have been created to maximize nutrient use efficiency and minimize environmental footprint:

Nano-fertilizers: They provide nutrients in the form of nano-particles so that nutrient uptake is more efficient and losses are minimized.

Controlled-Release Fertilizers (CRFs): These are made up of coated pellets that emit nutrients slowly, which is coordinated according to plant growth requirements.

Biofertilizers: Beneficial microorganisms such as Rhizobium, Azotobacter, or phosphate-solubilizing bacteria naturally improve the availability of nutrients.

Fertigation: Combining fertilizers with irrigation systems enables even distribution and greater uptake efficiency.

Application of AI and Drones: Aerial equipment and predictive analytics ensure timely and accurate dosage at the field level.

These improvements not only increase crop outputs but also guard water resources and soil health.

Conclusion

Mineral nutrition is a major support of plant physiology and ecologically sound agriculture. From the form of essential nutrients to mechanisms of uptake and transport, and to the influence of environmental and soil conditions, plant nutrition management is multifaceted but essential. Advancements in fertilizer technologies, knowledge on root–microbe interactions, and precision farming technologies provide the potential routes to optimizing nutrient use efficiency without sacrificing ecological harmony.

Through the arrangement of scientific information and sustainable technologies, we can satisfy increasing food production needs while protecting natural resources and enhancing climate-resilient cropping systems.

References

- Admin. (2021, January 17). Role of macronutrients and micronutrients. BYJUS. https://byjus.com/biology/role-of-micro-and-macronutrients/

- Agriculture :: Mineral Nutrition :: Introduction. (n.d.). http://www.agritech.tnau.ac.in/agriculture/agri_min_nutri_essentialelements.html

- Mechanism of uptake and transport of nutrient ions in plants. (2015, August 23). [Slide show]. SlideShare. https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/mechanism-of-uptake-and-transport-of-nutrient-ions-in-plants/51967600

- Saif_Ansari, Saif_Ansari, & Shikha, S. (2023, January 25). Uptake and translocation of mineral nutrients: mechanism of nutrient uptake, xylem loading, phloem unloading. Embibe Exams. https://www.embibe.com/exams/uptake-and-translocation-of-mineral-nutrients/

- Water transport in plants: Xylem | Organismal Biology. (n.d.). https://organismalbio.biosci.gatech.edu/nutrition-transport-and-homeostasis/plant-transport-processes-i/

- Manisha, M. (2016, December 12). Source and sink in Phloem translocation | Plant physiology. Biology Discussion. https://www.biologydiscussion.com/plant-physiology-2/phloem-transport/source-and-sink-in-phloem-translocation-plant-physiology/70606

- Singh, P., & Dadhe, B. L. (2022). Essential mineral nutrients for plant growth: nutrient functions and deficiency symptoms. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364936336_Essential_Mineral_Nutrients_for_Plant_Growth_Nutrient_Functions_and_Deficiency_Symptoms

- Soti, P. G., Jayachandran, K., Koptur, S., & Volin, J. C. (2015). Effect of soil pH on growth, nutrient uptake, and mycorrhizal colonization in exotic invasive Lygodium microphyllum. Plant Ecology, 216(7), 989–998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-015-0484-6

- Rona, & Rona. (2025, March 20). Understanding Nutrient Use Efficiency | ICL. ICL. https://icl-growingsolutions.com/agriculture/knowledge-hub/understanding-nutrient-use-efficiency/

- Asadu, C. O., Ezema, C. A., Ekwueme, B. N., Onu, C. E., Onoh, I. M., Adejoh, T., Ezeorba, T. P. C., Ogbonna, C. C., Otuh, P. I., Okoye, J. O., & Emmanuel, U. O. (2024). Enhanced efficiency fertilizers: Overview of production methods, materials used, nutrients release mechanisms, benefits and considerations. Environmental Pollution and Management, 1, 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epm.2024.07.002

- Campbell, A. (2024, October 23). Innovations in Fertilizer Management : How Technology is Making a Difference. Picketa Systems. https://www.picketa.com/post/innovations-in-fertilizer-management-how-technology-is-making-a-difference

- Patani, A., Prajapati, D., Shukla, K., Patel, M., Patani, P., Patel, A., & Singh, S. (2024). Environmental stress–induced alterations in the micro- and macronutrients status of plant. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 181–195). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-443-16082-0.00003-5